As the construction stage of The Whiteley, a major heritage redevelopment near Hyde Park, nears completion, the architectural team reflect on how Foster + Partners has integrated the London landmark’s textured history with contemporary principles and an ethic of sustainability.

9th April 2024

Heritage and Innovation: Reviving The Whiteley

The Whiteley is a building with a textured architectural history: of plans both real and imagined, inspired and curtailed, broken and repaired. Neither a discrete restoration project nor an empty site, the task of re-designing The Whiteley presented a particular challenge: that of historical interpretation and contemporary innovation. How could the heritage of the site be respected, while ensuring that the building met the highest sustainability standards possible? How could 150 years of history be expressed in an elegant and technically fluent design, without falling into the artificial, the inauthentic?

Historian and geographer David Lowenthal, often heralded as the founder of heritage studies, stated in a room of UNESCO representatives for the Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to World Heritage that architectural authenticity is “never absolute, always relative.” For an architectural team working on a project with heritage aspects today, Lowenthal’s recognition of relativity continues to resonate. It imagines a way of building where parts are connected and considered in terms of the whole, and where dialogues with the past, present, and future remain in open conversation.

This relativity was key in Foster + Partners’ design for The Whiteley – a 150-year-old, once-glittering department store that, until recently, was known as 'Whiteleys’. Located on the Bayswater edge of London’s Hyde Park, the practice was commissioned to revive the building as a mixed-use development including retail, leisure, and residential features. Before plans could be drawn, we needed to investigate the building’s patchwork of intersecting intentions and interventions. From the emergence of William Whiteley’s dream for a department store in the 1850s, to the major redevelopment that will reach the end of construction this year, much of this research was instrumental in establishing the groundwork for our design. There is no set formula; each feature of the project required a bespoke approach and reasoning – guided, but not fully defined – by its past lives. These aspects might seem to fit into a sense of ‘past,’ ‘present,’ or ‘future,’ but – as the structuring of this article suggests – are all connected across time.

Heritage is a relative act. A preservation effort that honours the past is also an investment in a sustainable future; the future-facing urban renewal of Bayswater calls back to Whiteley’s earliest visions for the site, 150 years before.

Imagining an ‘Immense Symposium’

In the summer of 1851, William Whiteley – a boy from Yorkshire, then only twenty years old – visited the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. A celebration of Britain’s colonial and economic success following the Industrial Revolution, the exhibition gathered ‘every conceivable invention,’ (as Queen Victoria wrote in her diary) – from folding pianos, to cutting-edge adding machines, to the largest diamond in the world. A symbol and endorsement of national pride at the height of the British Empire, the exhibition’s varying contents exemplified a modern faith in social, scientific, and artistic progress brought about by technological and geopolitical expansion. Over six million people are estimated to have visited – approximately one in four of the British population – from across all parts of the country, and all social classes.

An exterior illustration of Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London (1851). One of a series of drawings by Joseph Nash, Louis Haghe, and David Roberts from Dickinsons’ Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, published by Dickinson, Brothers, Her Majesty’s Publishers (London, 1852).

As an architectural endeavour, the ‘Crystal Palace’ was an immediate success. The gigantic glass building was designed and built by Joseph Paxton in 1851 and took inspiration from the glass of the garden houses that he had previously designed for the Duke of Devonshire. The structure covered eighteen acres of Hyde Park and housed 14,000 exhibitions and 100,000 objects from across the world. It was this context, this vast and proliferating emporium – “one of my favourite buildings,” writes Norman Foster – that William Whiteley encountered.

In 1863, over a decade after his visit, Whiteley established a drapery shop at 31 Westbourne Grove. In 1867, this had matured to seventeen ‘department’-style shops on the same street; by 1872, the store, by now known as Whiteleys, had expanded beyond drapery to offer ‘an immense symposium’ of goods – with Whiteley once boldly claiming that he could provide anything from a door pin to an elephant. Supposedly the target of disgruntled competitors, the successful Westbourne stores were subject to various arson attacks and were burned to the ground in 1887. This did not halt the project, but rather galvanised Whiteley’s ambition; the stores were rebuilt, and Queen Victoria awarded Whiteleys a Royal Warrant in 1896 – a privilege reserved for few businesses.

William Whiteley set up his store in a single drapery shop in 31 Westbourne Grove in 1863. By 1867, his business occupied a row of shops along Westbourne Grove, comprising seventeen separate departments. The warehouse – where Whiteleys department store was soon built – was on the ‘block’ behind this street.

William Whiteley set up his store in a single drapery shop in 31 Westbourne Grove in 1863. By 1867, his business occupied a row of shops along Westbourne Grove, comprising seventeen separate departments. The warehouse – where Whiteleys department store was soon built – was on the ‘block’ behind this street.

The establishment’s urban configuration – the stores on Westbourne Grove and a warehouse on Queensway (then ‘Queens Road’), which incidentally connects with Hyde Park and with the memory of Paxton’s Palace – remained for a further decade. In 1907, Whiteley was shot and killed (allegedly by an illegitimate son) before he could see realised the next phase of his ambitions for the growing enterprise. However, despite his death, Whiteley’s ample fortune meant that his grander aspirations could yet become a reality. The company’s board soon decided to move the business to a new purpose-built store on Queensway, next to the existing warehouses.

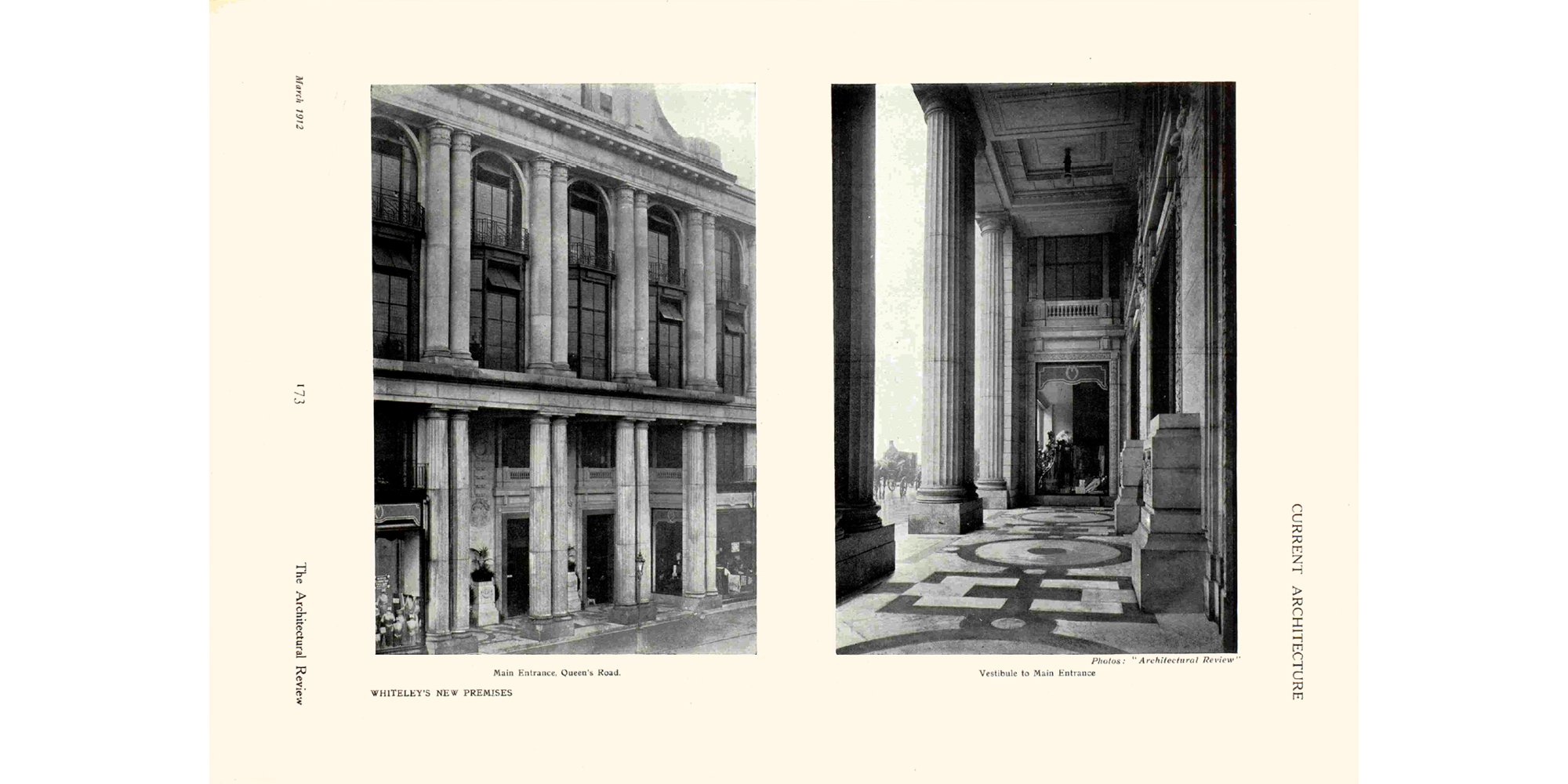

An Englishman, John Belcher, and a Scot, John James Joass, both notable architects of their day, were commissioned to design the new store. Belcher had recently designed Chartered Accountants Hall (1890), one of the first neo-Baroque buildings in London, and was already established as a lavish Edwardian municipal architect. In 1905, Joass was made a partner in Belcher’s practice and worked on projects including the Royal Insurance Buildings on St James's Street and Piccadilly (1909), and later on, the re-building of the Swan and Edgar department store (1919) at Piccadilly Circus. The pair’s design for Whiteleys had to rival the likes of Harrods (designed by Charles William Stephens and opened in 1905) and Selfridges (designed by Daniel Burnham and opened in 1909).

Belcher, Joass, Curtis Green: Moving to Queensway

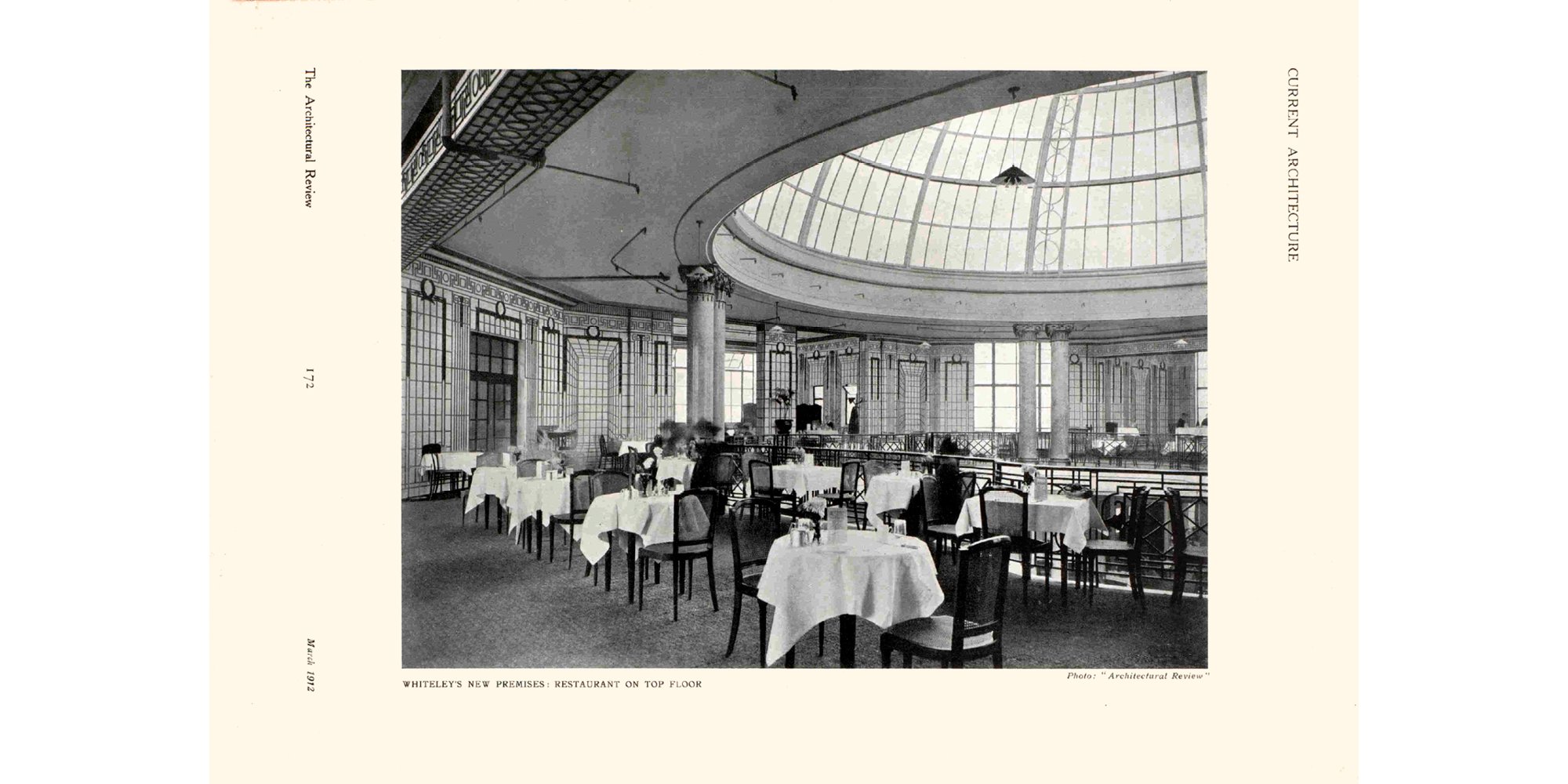

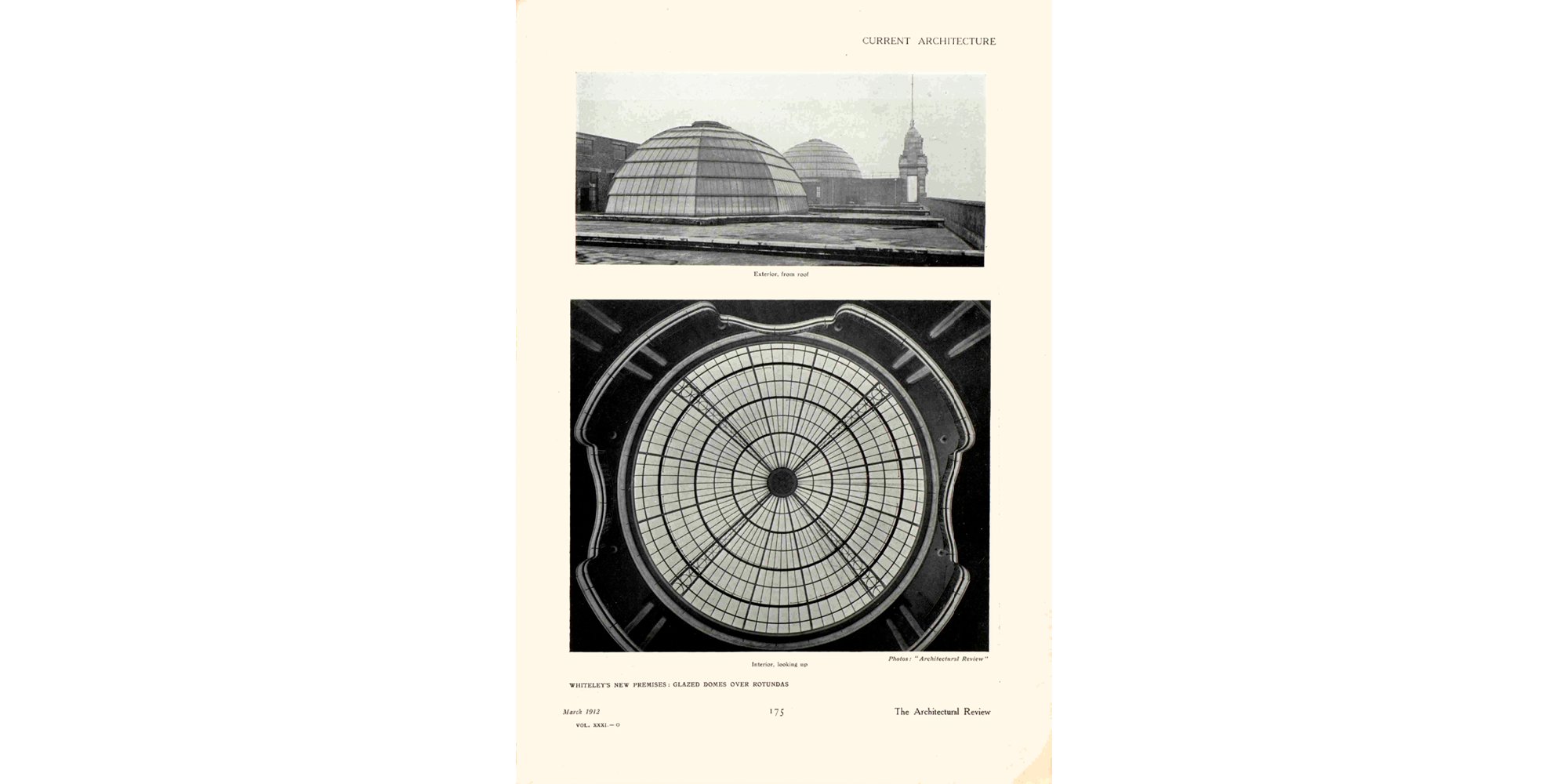

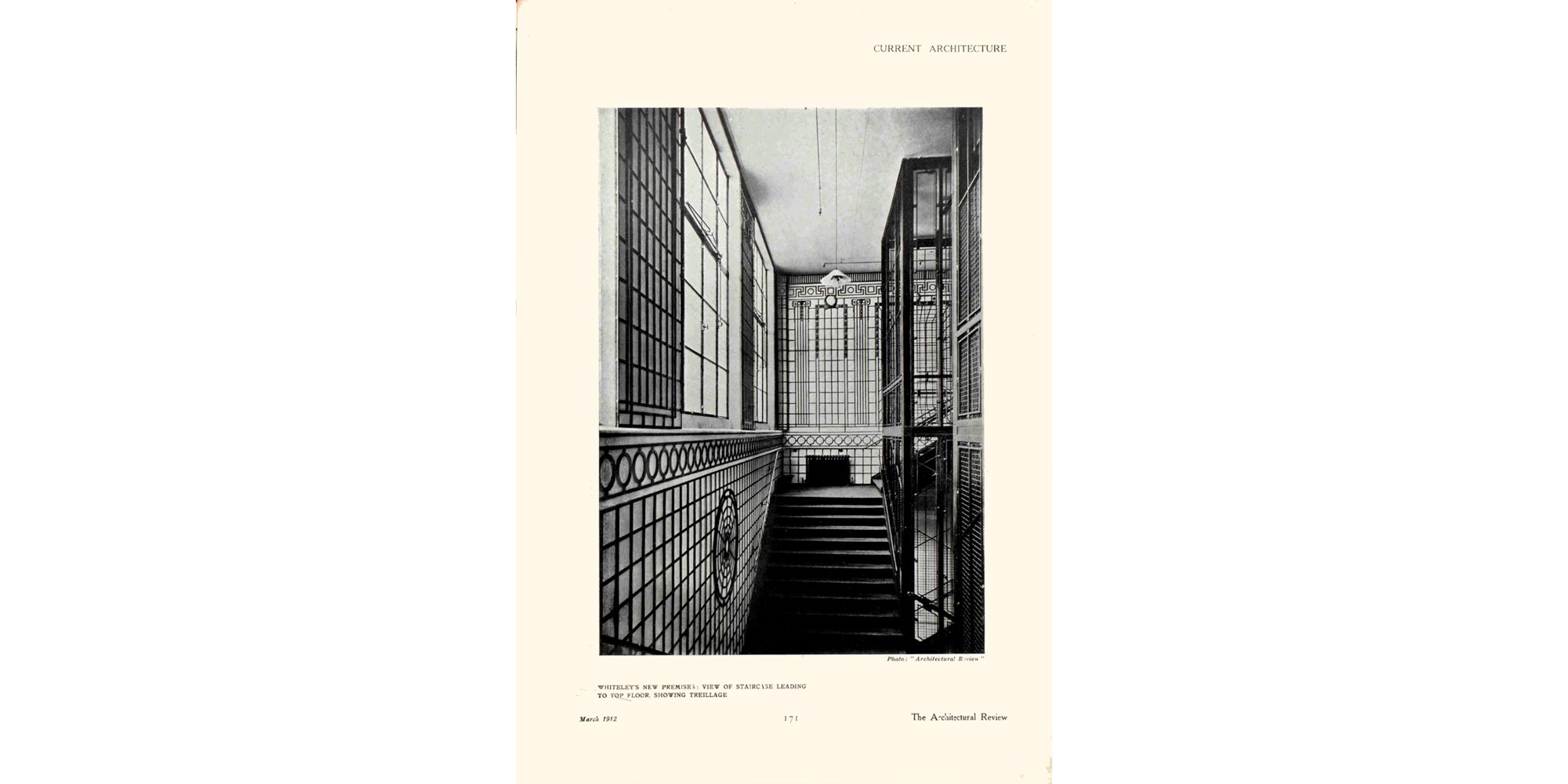

Belcher and Joass envisioned a symmetrical design, hailing from an appreciation of classical forms. The building's prevailing feature was a central dome, which brought natural light into the deep-plan store and added ‘an air of dignity to the shop,’ as The Architectural Review reported in March 1912.

Sadly, not all of Belcher and Joass’s plan was realised. Two cupolas were designed for the northern and southern corners of Queen’s Road; however, due to the load-bearing restrictions on the Victorian warehouses on the northern end, only the southern cupola was built. Additionally, their drawings depict Italianate roof gardens with glazed pavilions designed in the form of classical orangeries, for example, which would have provided a mixture of outdoor and indoor leisure space for visitors. Roof gardens, in particular, would have been a distinctive and exceptionally unusual proposition for the time – given their proposal to extend the public realm to the top of an essentially private building.

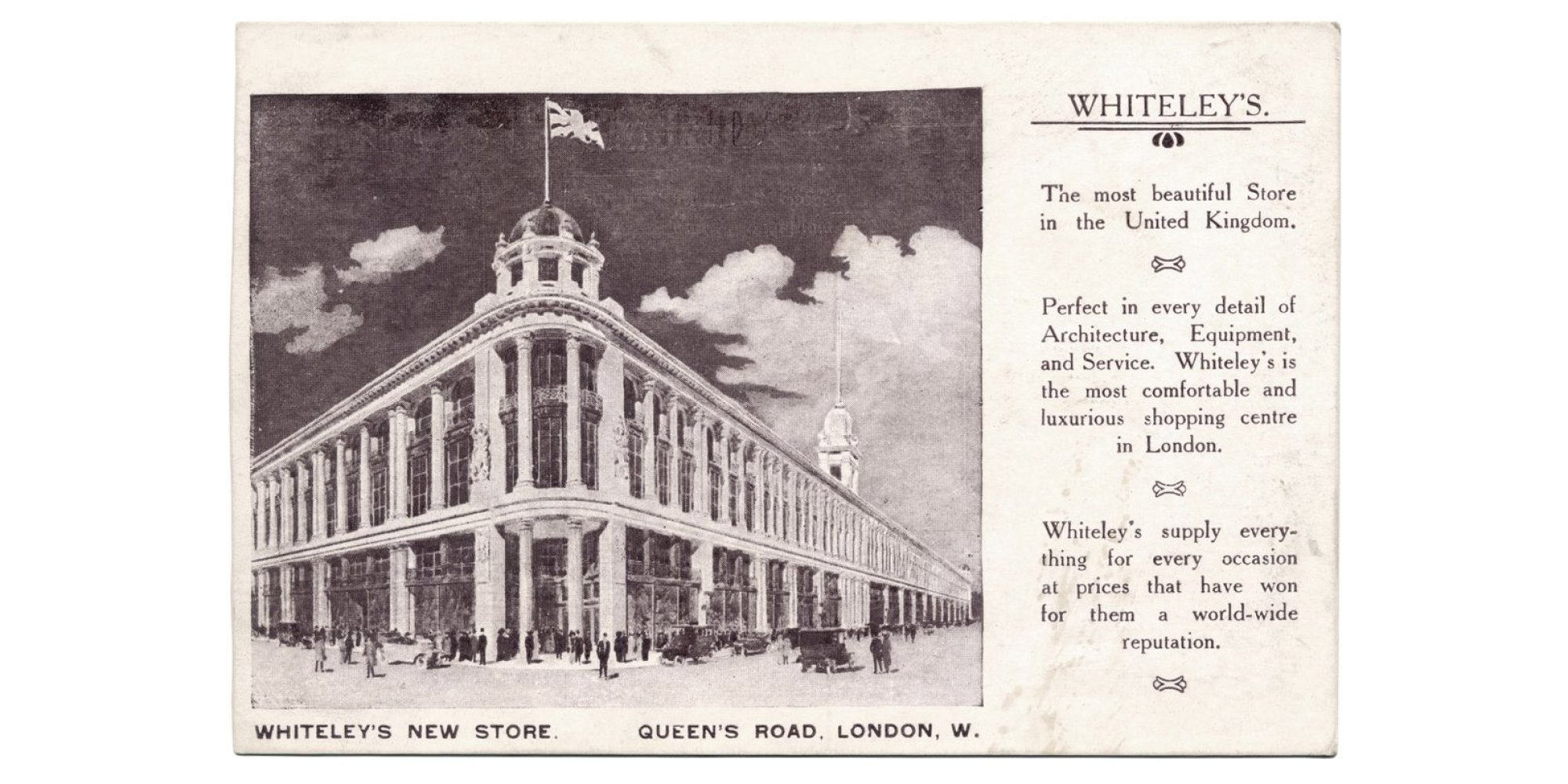

This first development of Whiteleys was opened by the Lord Mayor of London on 2 November 1911. At the time, it was claimed to be ‘the largest shop in the world’, ‘the most beautiful store in the United Kingdom’, and ‘perfect in every detail of Architecture, Equipment, and Service.’

Whiteleys, though commercially successful, was not universally considered as architecturally fluent. Belcher died in 1913 and, while the first phase of the design was completed, his grand unified idea was never realised. William Curtis Green, who had been articled to Belcher, was later commissioned to complete the much compromised and redesigned second phase between 1925 and 1927. Although Curtis Green followed the architectural language defined by Belcher and Joass, the full symmetry and continuity of the original scheme was never achieved. He was limited by parts of the old Victorian warehouse buildings that had remained from the 1880s, which constrained his design to the different floor levels; the Northern cupola couldn’t be executed either due to the load constraints that these Victorian buildings imposed.

Whiteleys changed hands over the decades. In 1927, shortly after the Curtis-Green-designed development finished, the site was purchased by Harry Gordon Selfridge. It was then bombed during an air raid on 19 October 1940, and subsequently purchased by United Drapery Stores in 1961, a retail group that dominated the British high street from the 1950s to the 1980s. The building later achieved Grade-II-listed status in 1970 but closed in 1981, falling into a state of disrepair, with severe water damage and vandalism enacted on the site. Decades of incremental, inconsistent, and often unsympathetic repairs further distanced the project from the vision of the early twentieth-century original.

Recovering somewhat by the twenty-first century, the building and its tenants were hit once again, this time by the 2008 financial crisis. After the site’s purchase by Meyer Bergman in 2013, and following a successful design competition, Foster + Partners was commissioned to return and elevate ‘The Whiteley’ (a subtle renaming of Whiteleys) to its former glory – this time with a more contemporary mixed-use programme that includes retail, residential, leisure, hotel, and public space. Construction began in 2018 and is set to complete in 2024.

Designing History

The Whiteley is a Grade-II-listed building. Listing protects the fundamental aspects of a building’s physical character and historical significance, while allowing scope for sensitive intervention that brings a building up to contemporary standards. When working with a listed property, comprehensive historic and archival research is undertaken before certain architectural decisions are formed and plans proposed.

Even the task of establishing a linear history of the site proved tricky; site visits revealed details that had circumvented plans and presented as many unknowns as knowns. Demanding far more than a simplistic restoration of the facade, the redevelopment of The Whiteley required the formation of a critical framework that could unite this narrative patchwork of a building and competently ensure standardisation to replicate historical methodologies. This framework needed to incorporate a sensitive heritage lens with the sustainable, integrated, forward-thinking design approach for which Foster + Partners is renowned. Accordingly, and rather than developing a blanket solution, we worked closely with a plethora of specialists to develop a robust and sensitively crafted design – one being Tom Burke, Head of Conservation Design and Sustainability at Westminster City Council. Assembling these integrated, cross-disciplinary teams was essential in realising a project of such craft, authenticity, and historical significance to London.

As with all heritage projects, the design process required a complex negotiation of and stake in an understanding of history itself – what it means, and how it relates to the present day. The architectural team had to grasp this history while adapting and updating the building to meet modern standards and contemporary sustainability requirements, with formal elegance and technical fluency. What version of the building’s complicated past was it set to inherit (or override), and where could interventions be made – either as authentic continuations or innovative additions to the structure?

The Whiteley Past: Returning to Material and Graphical Origin

Certain aspects of the project, in line with the guidance of its Grade II heritage listing, required a respectfully pure preservation approach. This was the case for Whiteleys’ iconic facade, with its ornamental detailing and glazing as laid out in the original 1911 structure. According to The Architectural Review in 1912, the stone of the facade was a mixture of Cornish grey granite and Portland stone (some from quarries that have since been decommissioned or fully excavated), with sculptural additions by ‘Mr. Crosland McLure and Mr. Broadbent,’ and ivory-glazed brickwork by Leeds Fireclay Co. The facade tells an irreplicable story of stonemasonry at the turn of the century and references a range of industrial and artisanal hubs that had emerged across Britain. More locally, it bears the marks of weather and age from the past one hundred and thirteen years spent as witness to Bayswater’s rapidly changing urban fabric.

The Whiteley’s Portland stone and Cornish granite materials were preserved wherever possible. If they could not remain in place they were carefully re-located and re-purposed across the site, with the guidance and expertise of stonemasons. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

The Whiteley’s Portland stone and Cornish granite materials were preserved wherever possible. If they could not remain in place they were carefully re-located and re-purposed across the site, with the guidance and expertise of stonemasons. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

The Whiteley’s Portland stone and Cornish granite materials were preserved wherever possible. If they could not remain in place they were carefully re-located and re-purposed across the site, with the guidance and expertise of stonemasons. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Wherever possible, this stone was preserved – with preservation implying respect for the original materials and their designated placement – thus aligning with the original intentions of the craftsman who laid them there. Some stones, because of their degraded structural properties, could not be preserved in such a way. Instead, a conservation approach – implying an appropriate, and flexible use of existing materials – was employed. In this case (and going beyond the base-level requirements outlined by Historic England) we collaborated with specialist stonemasons to repurpose the heritage material elsewhere in the building. This required extremely close attention to context; stone from the south-facing portion of the building that had weathered in a particular way, for example, continued to face south even if it had been relocated. Additionally, the statues depicting the four seasons placed at the entrance, and the impressive stone clock that hailed the 1911 opening, were carefully stored and protected during the construction phase, and later returned.

Conservation, in understanding and respecting the original building, is also, crucially, a sustainable practice; it reduces the embodied carbon involved in construction, prevents waste, and extends the lifespan of a pre-existing building far beyond that of its original architects’ intention. As the RIBA notes in their recent heritage guidelines: ‘Conserving energy, conserving building fabric, conserving resources and conserving heritage skills are part of the same project: addressing the climate emergency through sustaining cultural value.’

Sometimes, a commitment to the history of a building involves understanding what has been repressed, denied, or rendered impossible, and reconsidering these constraints in the present day. Sustaining cultural value in this way was a key motivation for the introduction of the unrealised northern cupola, which finally brought a symmetry to the site that Belcher and Joass had desired but could not fulfil. The northern cupola is an acknowledgement of the potential of the 1911 plans and is, today, a perfect companion the carefully-restored southern original.

Though Foster + Partners built the northern cupola anew, we ensured that its mirroring aesthetic to the southern cupola was as authentic as possible. Sometimes, technology was employed to support this; stonemasons scanned the existing lion’s head sculptures on the southern cupola, for example, enabling them to print a three-dimensional replica for the sculptors to work from.

The Whiteley Present: Continuing Patterns, Ideas, Materials

The practice employed for the new northern cupola is a perfect example of Lowenthal’s theory of heritage as a relative, interpretive act that can “be understood as a form of culture – another aspect of modernity of our time.” However, as well as consulting Belcher and Joass’s original plans and materials, we had to think creatively about the present condition of the site and how our interventions conserved, extended or interpreted its history.

The iron balustrades that cover the glazed facade are one key example of this. These had heavily rusted over the decades, and their dimensions no longer fit modern building safety regulations. These balustrades were listed but could not safely operate on a new structure. Following extensive discussions with the local council, and based on the condition surveys that deemed them too low in height and unsafe in material composition, the balustrades were approved for a redesign.

The iron was removed, smelted and mixed with other alloys. With the aid of skilled blacksmiths, this ‘new’ iron was recast in a mould with a pattern replicating Belcher and Joass’s illustrations that would also conform to modern safety dimensions. Rather than prefabricating anonymous balustrades from scratch, this method brought the architects closer to the artisanal processes that would have been used in 1911 (perhaps even in the construction of the Crystal Palace in 1851).

Honouring existing materials was important to this project. However, and as Pamela Jones comments in The Journal of Preservation Technology: ‘Authenticity is a concept much larger than material integrity.’ This was the case for the windows, where the original frames and glazing had long become unsuitable – with many panes broken, vandalised, and not up to modern thermal or acoustic standards. The windows – like the balustrades – are major characters in The Whiteley’s visual effect; it was imperative to agree on a heritage strategy that negotiated their reimagining with sensitivity. As the originals were deemed to be beyond re-use, we had to update the facade. The windows were replicated in the same material, steel, with like-for-like dimensions that remained faithful to the proportions of the originals, while delivering excellent thermal and acoustic insulation.

Analysis was also undertaken on the paintwork, which has been layered over the years. Unpeeling the layers of paint, we recovered an original shade of grey, as painted in 1911. This was then colour-matched and applied to all the windows. Colour – as well as structure and detailing – is another way that a building might relate to its former self. This is an avenue of heritage practice that calls upon contemporary analytical methods to uncover and access an architectural history.

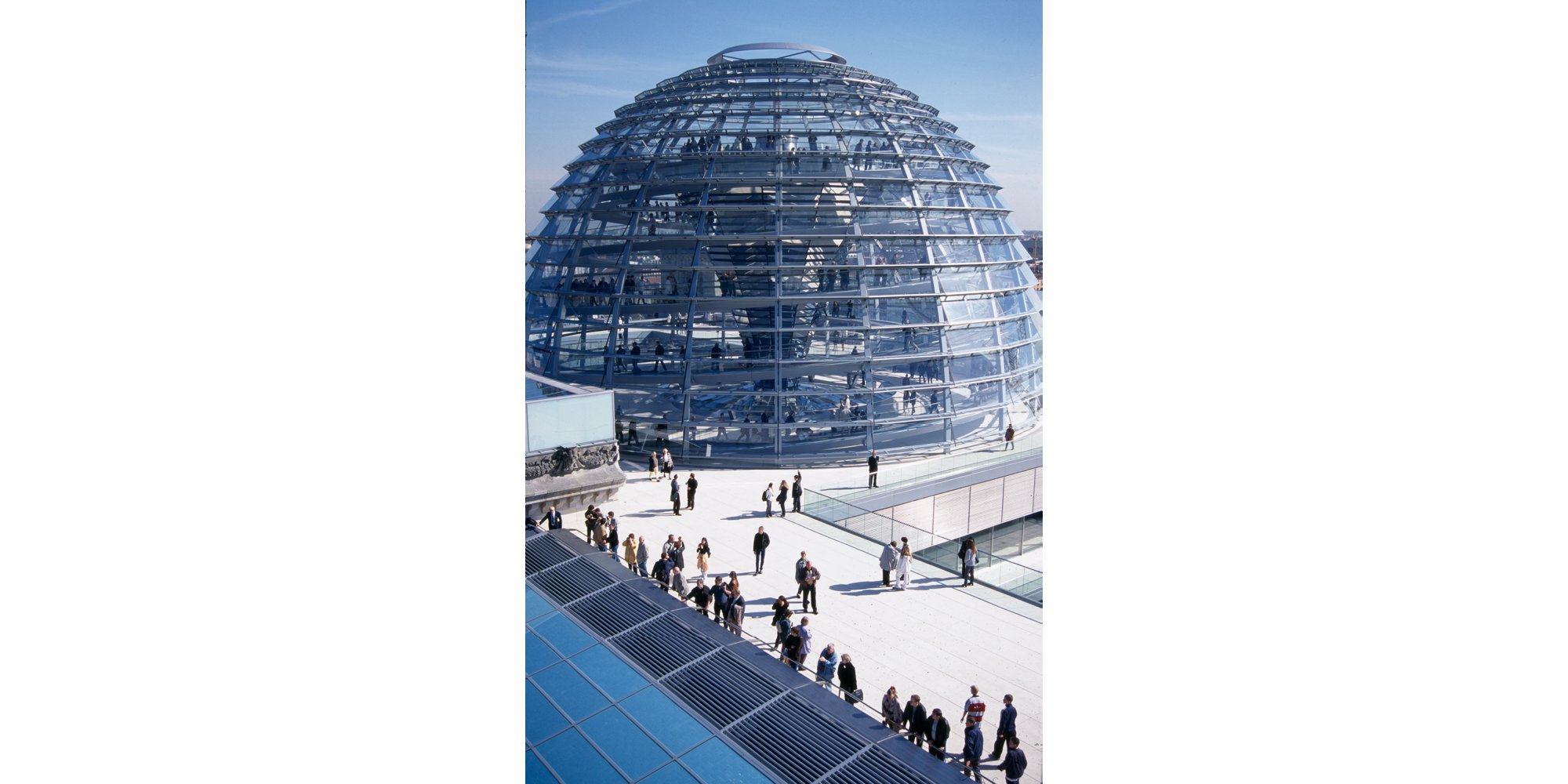

This application of modern technology in service of a building’s history is epitomised in The Whiteley’s central, double-skin dome, a structure that sits atop the atrium space and is synonymous with the building. This dome’s profile and glazing are congruent with the original (down to the detail level of replicating the same joints). However, the updated Whiteley dome is placed at a higher level than the original, making it newly visible from vantage points across London. Similar strategies of identity and placemaking can be found across Foster + Partner’s heritage work, from the roof of the Great Court at the British Museum (1999) through to the dome that tops the Reichstag in Berlin (1998).

The Great Court at the British Museum (1999) reimagined the formerly inaccessible courtyard, creating an atrium for visitors to walk through. The glass roof was a key strategy in doing this; it lightened the space, and deftly incorporated the museum’s heritage structures with a future-gazing ideal of opening the museum to all. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The dome of the Reichstag (1998) was radical in its architectural opening and ‘lightening’ of the German parliament, the Bundestag, at the end of the century in a reunified Berlin. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The Whiteley Future: Imagining a New Urban Realm

For a building that had so long been out of place, proportion, and time, our vision was to make The Whiteley once again commensurate with its physical and psychological presence. Different aspects of the building will serve different functions – some for the first time in the building’s history. The original heritage entrance screen (of three separate entrance doors at the centre of the facade) was conceived by Belcher and Joass to create a discrete and perhaps domestic scale entrance to the interior world of the department store. This was something of a theatrical device used to separate shoppers from the urban realm and absorb them into another, more fantastical space. Today, this style of entrance does not function well as a method for urban connectivity. It does, however, work elegantly for other types of use and setting. The heritage screen has therefore been re-purposed and relocated to become the entrance to the new Six Senses hotel (the first in the United Kingdom) on the Redan Place edge of the development, on the northern side of Queensway. This entrance, as it did a century ago, is perfectly suited to offer a more intimate and slower-paced arrival experience. Inside, the restored marble heritage staircase is celebrated, connecting the hotel to the history of the overall project.

Visualisations of The Whiteley’s exterior and interior connect people from the urban realm with the building. A key part of this is the ‘opening’ of the main entrance. Belcher and Joass used three separate doors; Foster + Partners has retained the original columns of the entrance but have removed these doors, opening to an atrium that better connects the inside with the outside. A circular flexible event space, mapped by the dome above, heralds this new connectivity. © Foster + Partners

Visualisations of The Whiteley’s exterior and interior connect people from the urban realm with the building. A key part of this is the ‘opening’ of the main entrance. Belcher and Joass used three separate doors; Foster + Partners has retained the original columns of the entrance but have removed these doors, opening to an atrium that better connects the inside with the outside. A circular flexible event space, mapped by the dome above, heralds this new connectivity. © Foster + Partners

Beyond the immediate built envelope, which required extensive consideration, the regeneration of The Whiteley has been a truly unique opportunity to transform an entire neighbourhood in the heart of London and imagine a newly enhanced civic role for Bayswater. The creation of the public courtyard is a key tenet of this vision of the future. Carefully designed to maximise daylight, the courtyard will offer a sequence of arrival spaces that enable a more open and accessible connection and extension of the public realm. As Patrick Campbell, project lead for The Whiteley, comments:

The Whiteley began as a wonderful theatre of retail — of experience. However, over time its various interpretations have contributed less and less to the neighbourhood. We wanted to radically rethink how that building worked, and so designed an extraordinary new public space that draws people from the street. It is all about about bringing light, landscape, and people together.

Patrick Campbell, Senior Partner, Foster + Partners

The Whiteley is testament to the fact that heritage architecture need not be confined to the past or to a single function. To achieve such a complex programme, these heritage projects require their architects, patrons, craftsmen, interpreters, and legislators to endorse and create an elegant and sustainable structure. Architectural design is as much about the granularity of preservation and construction methods as it is an interpretation of a more abstract history and an imagining of the future; it is also invariably a result of the people who steer the projects from conception to completion.

From William Whiteley’s vision in the 1860s to The Whiteley of today, Foster + Partners has delivered a historically sensitive project that upholds a forward-facing philosophy of sustainable and considerate urban planning. In a way that is ‘never absolute, always relative,’ our architectural strategy brings The Whiteley's past, present, and future into a coherent, elegant, and sustainable whole.

Author

Yannis Hajigeorgis

Author Bio

Yannis is a Associate Architect at Foster + Partners. He worked and studied in the UK and in Italy, before moving to London and joining the practice in 2018. Yannis has worked on a range of projects, most recently focusing on adaptive reuse of heritage buildings in Central London, where he brings a robust detail-orientated and practical approach to his designs, with a strong commitment to sustainability. Yannis also enjoys mentoring and takes part in the practice's mentoring programme which is designed to support colleagues with professional career growth.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George