Adaptive re-use is a growing field in architecture that finds new purposes for existing buildings. Spanning disciplines and techniques, negotiating history and contemporaneity, it is a particularly hybridist design approach. Several adaptive re-use projects by Foster + Partners reveal the complex demands and possibilities of working with existing buildings, and how they offer more sustainable ways of building.

25th November 2024

The Science and Art of Adaptive Re-use

One of the most important questions facing architects today is how to engage with a building that already exists – a building that was likely designed by other architects, perhaps when needs and values were different. As the Royal Institute of British Architects states: 'More than one in five buildings in the UK pre-date 1919 and 40 percent of construction activity relates to the maintenance, renovation or restoration of existing buildings.’ The question of what to do with these buildings, and how we make these decisions sustainable, extends worldwide. As populations grow and successive generations each find new ways and sites to develop, our towns and cities have both densified and sprawled; simultaneously, many of these existing buildings are unoccupied, environmentally inefficient, or poorly managed. The need to engage intelligently with existing buildings – at an architectural, social, and environmental level – is more apparent than ever.

Fred Scott’s On Altering Architecture opens with a clarifying statement on the built environment: ‘All buildings […] have three possible fates, namely to remain unchanged, to be altered, or to be demolished.’ In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, of the three ‘fates’ Scott refers to, demolition and remaining unchanged were the preferred mechanisms for dealing with existing buildings. Demolition is sometimes unavoidable: a building might be unsafe, beyond repair, or unable to reasonably keep pace with contemporary requirements. However, in the twenty-first century, and due to the increasing scrutiny on the validity of new buildings in the climate crisis, demolition should not be a default. To ‘remain unchanged’ – or what might commonly be thought of as ‘preservation’ – presented itself as an antidote. However, as Bie Plevoets and Keonraad Van Cleempoel explain in their theoretical introduction to Adaptive Use of the Built Heritage: ‘The widening scope of heritage conservation makes it impossible to [preserve] all heritage aspects in a strictly restorative manner.’ Besides, preservation is not necessarily the right answer if a building has already become stranded, inefficient, or its old purpose is no longer viable.

Strict preservation can risk freezing a building in the past and alienating it from contemporary and future users, while outright demolition risks losing a building altogether. In the space between these two poles, Scott’s third option of ‘alteration’ – of adaptive re-use – emerges. Adaptive re-use is the practice of modifying existing buildings to fulfil a function that is different from that originally intended, ideally in ways that acknowledge the history of a structure and its surroundings while bringing about necessary environmental and structural updates. A design approach that has grown in momentum over the past few decades, adaptive re-use seeks to extend a building’s lifespan and challenges architects to think creatively about how existing and future designs can interact.

As the United Nations Environment Program reports: ‘The buildings and construction sector is by far the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, accounting for a staggering 37% of global emissions.’ Adapting existing buildings is a crucial route to meeting our net-zero carbon targets, given that it is often (though not always) a less resource- and energy-intensive way of building.

Three formative projects that introduce the practice’s approach to designing with historic buildings: the Sackler Galleries at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (1991), The Reichstag, New German Parliament, Berlin (1998) and the Great Court at the British Museum, London (1999).

Three formative projects that introduce the practice’s approach to designing with historic buildings: the Sackler Galleries at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (1991), The Reichstag, New German Parliament, Berlin (1998) and the Great Court at the British Museum, London (1999).

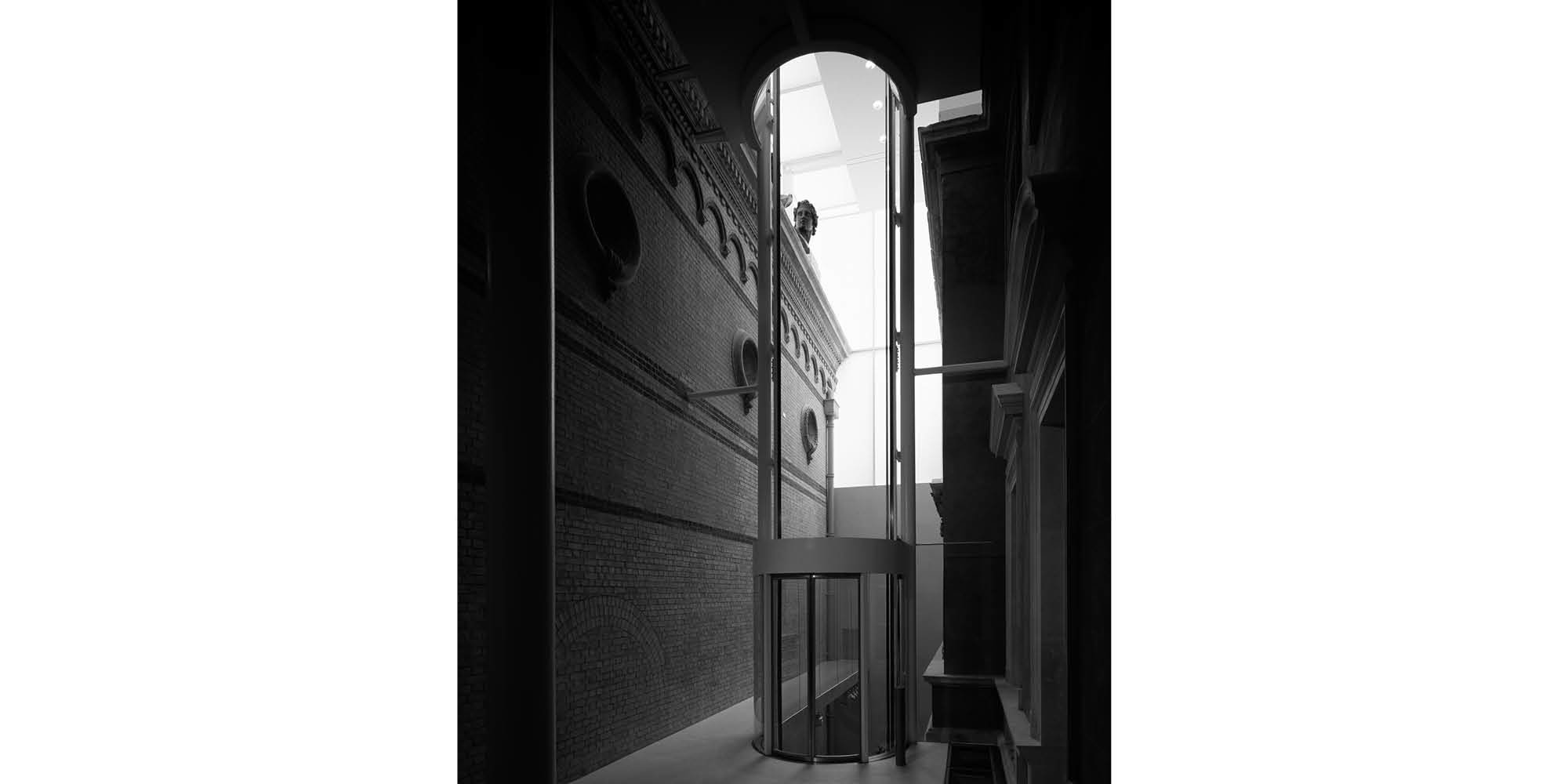

Over several decades, Foster + Partners has worked with many existing structures. This experience began with the Sackler Galleries for the Royal Academy of Arts in London (1985-1991) and evolved through projects of ever-growing complexity, like the Reichstag in Berlin (1992-1998) or Great Court at the British Museum, London (1994-1999). While these projects did not involve a change of use – instead modernising and expanding spaces, programmes and amenities of existing historic structures and institutions – they did formalise a philosophy that has informed Foster + Partners’ approach to today’s agenda of adaptive re-use.

Underpinning this philosophy is the belief that even the most notable historic structures are often the product of multiple interventions over years, decades or centuries. As Norman Foster describes: ‘Such buildings are like a city in microcosm as they reveal layers of history through the modifications and additions made during different periods in time. Our philosophy to follow this rationale with interventions in a contemporary manner seems, in retrospect, to be logical and traditional.’ In support of this, Paul Goldberger would write of the practice’s Sackler Galleries in his book ‘Building with History:’ a building like the Royal Academy ‘had been accruing elements for most of its life and had absorbed them into an evolving, hybrid form’ and, with this, ‘a light, tensile and elegant Modernism could simply become another element in the ongoing dialogue that the building represented.’

This intelligent, intentional and interventionalist philosophy of preservation through evolution – to build with history, as Goldberger explains, ‘as a way of looking forward, not backwards’ – would be a particularly appropriate philosophical grounding for the often more complex typological change inherent in the process of adaptive re-use. Advancing this approach, Foster + Partners has transformed a number of existing buildings into a wide range of ‘hybrid forms,’ or new uses altogether. The following three projects – The Murray in Hong Kong, Ombú in Madrid, and Apple Tower Theater in Los Angeles – capture a cross-section of this range. Though different in site, scale, and purpose, all rise to the challenge of adaptive re-use.

Part 1: Vacated Government Office to World-class Hotel

Foster + Partners’ reimagining of the Murray Building in Hong Kong, which began in 2013 and completed in 2018, is the story of a vacated office building finding new purpose as a leading hotel, now known simply as The Murray. From the onset, the Foster + Partners design team, alongside the client, wanted to celebrate the original, protected structure, while also creating a bespoke, twenty-first-century experience within. How could such a building change use while retaining its character and ethos? And how could these design decisions be traced and justified? The resulting project – like the Sackler Galleries over 25 years earlier – is a sensitive balancing of old and new, a practice of innovation and retention. In a departure from those early projects of building with history, however, The Murray is also a story of transformation.

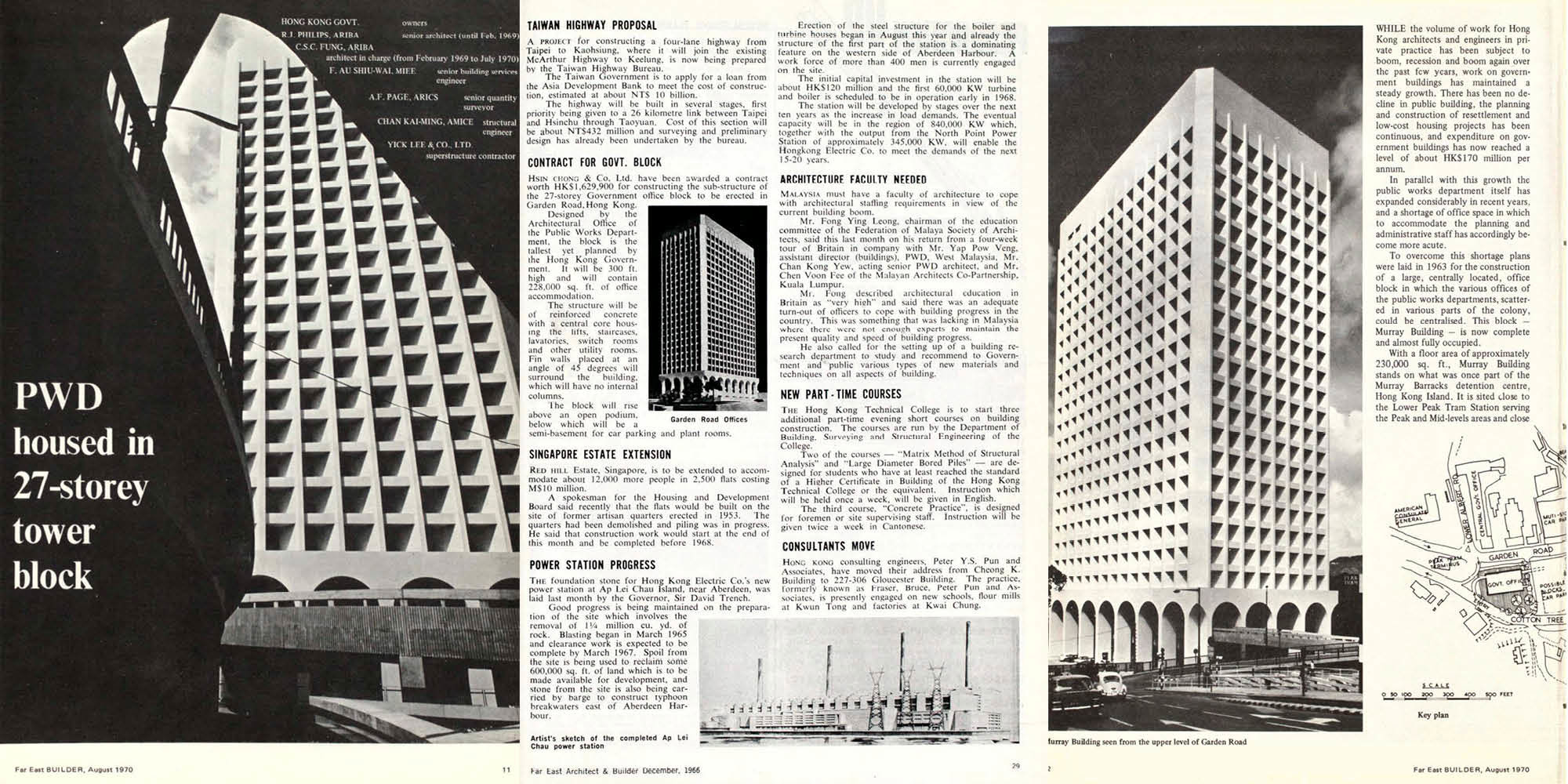

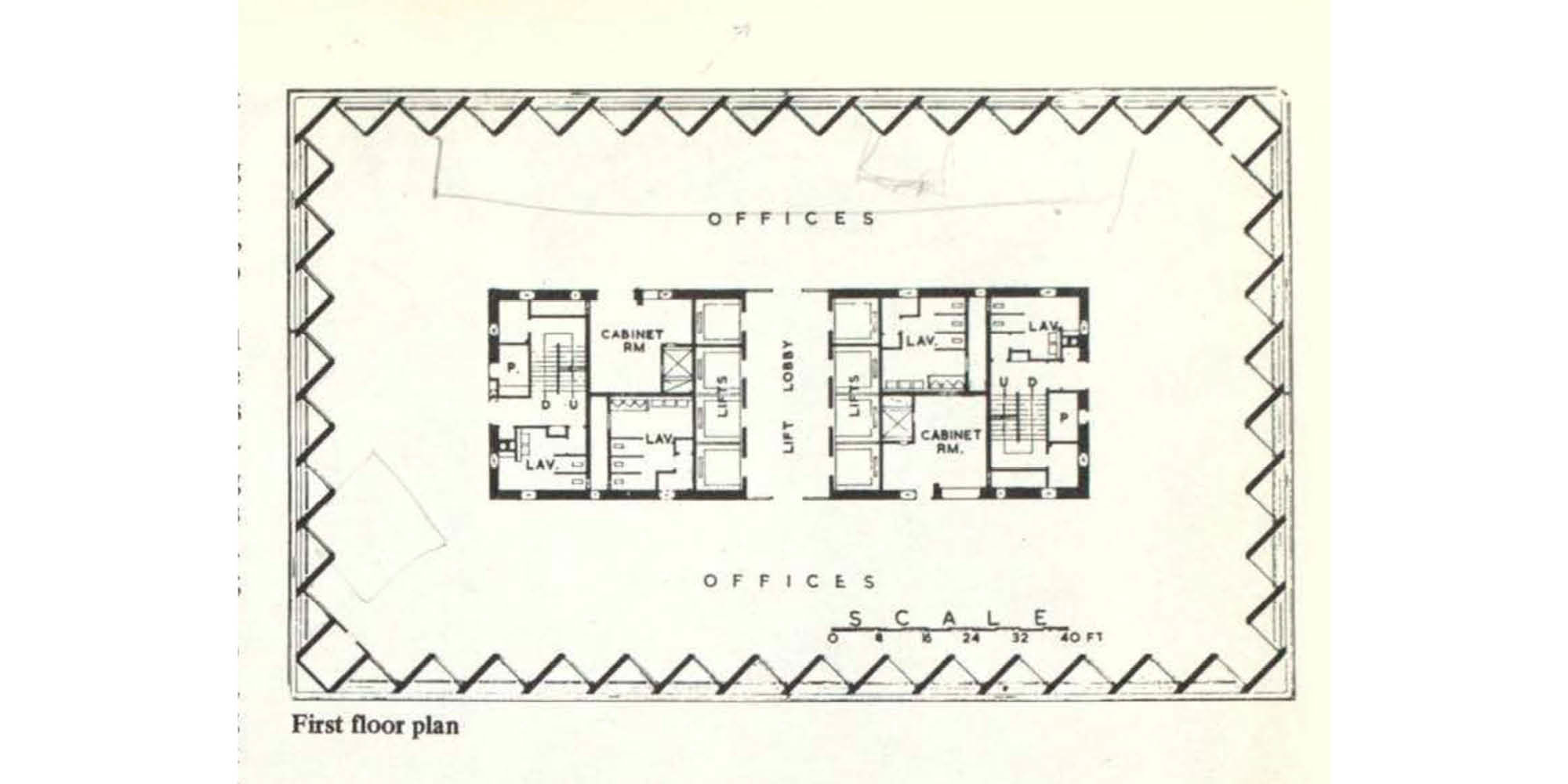

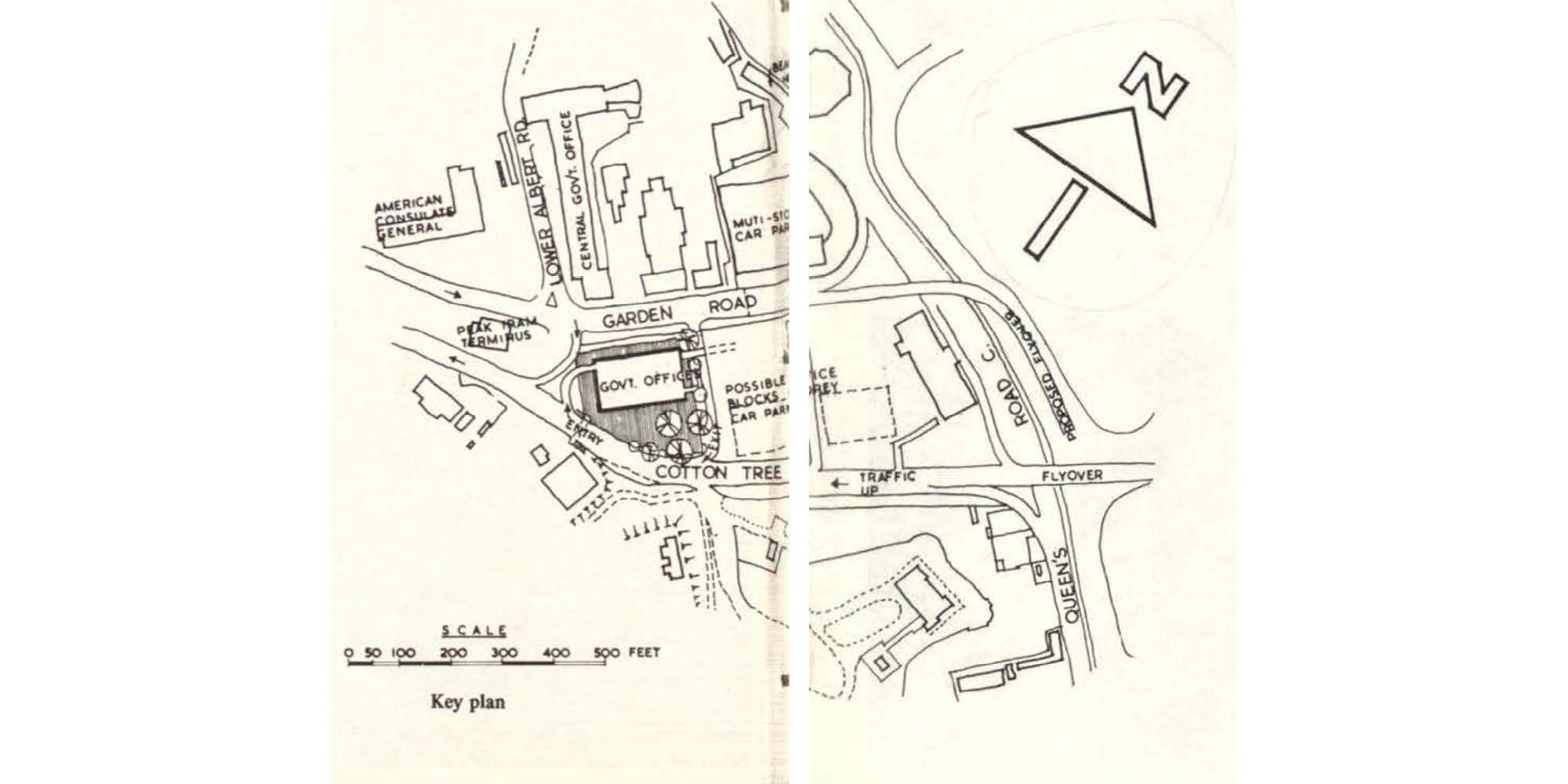

In 1967, the British government commissioned city planner Ron Phillips to design a tower block for the Hong Kong Public Works Department. This was an era when Hong Kong was rapidly expanding and, in response, at the time of opening the twenty-seven-storey tower block was the tallest in the city and an exemplar of a Modern style of office design.

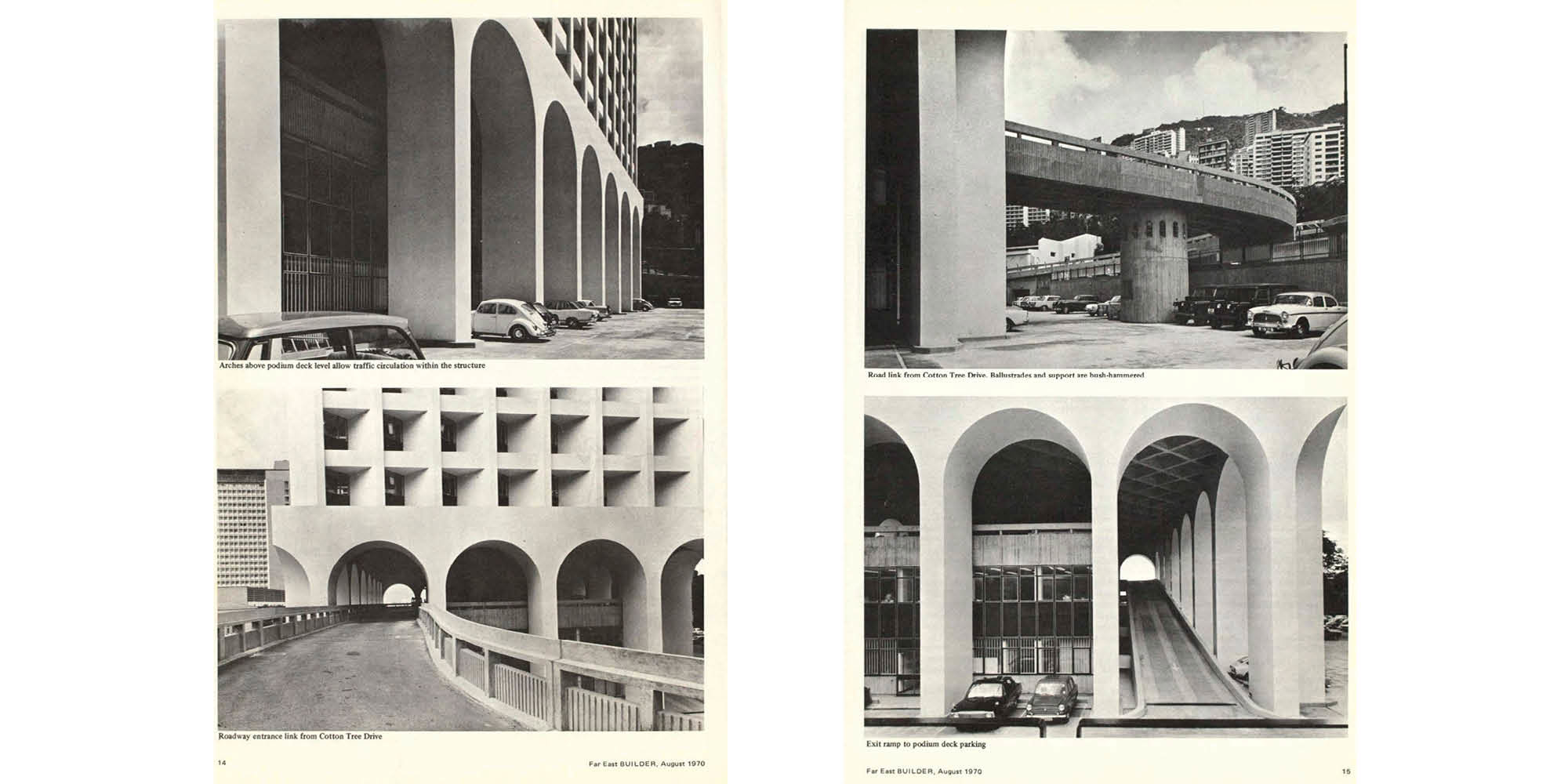

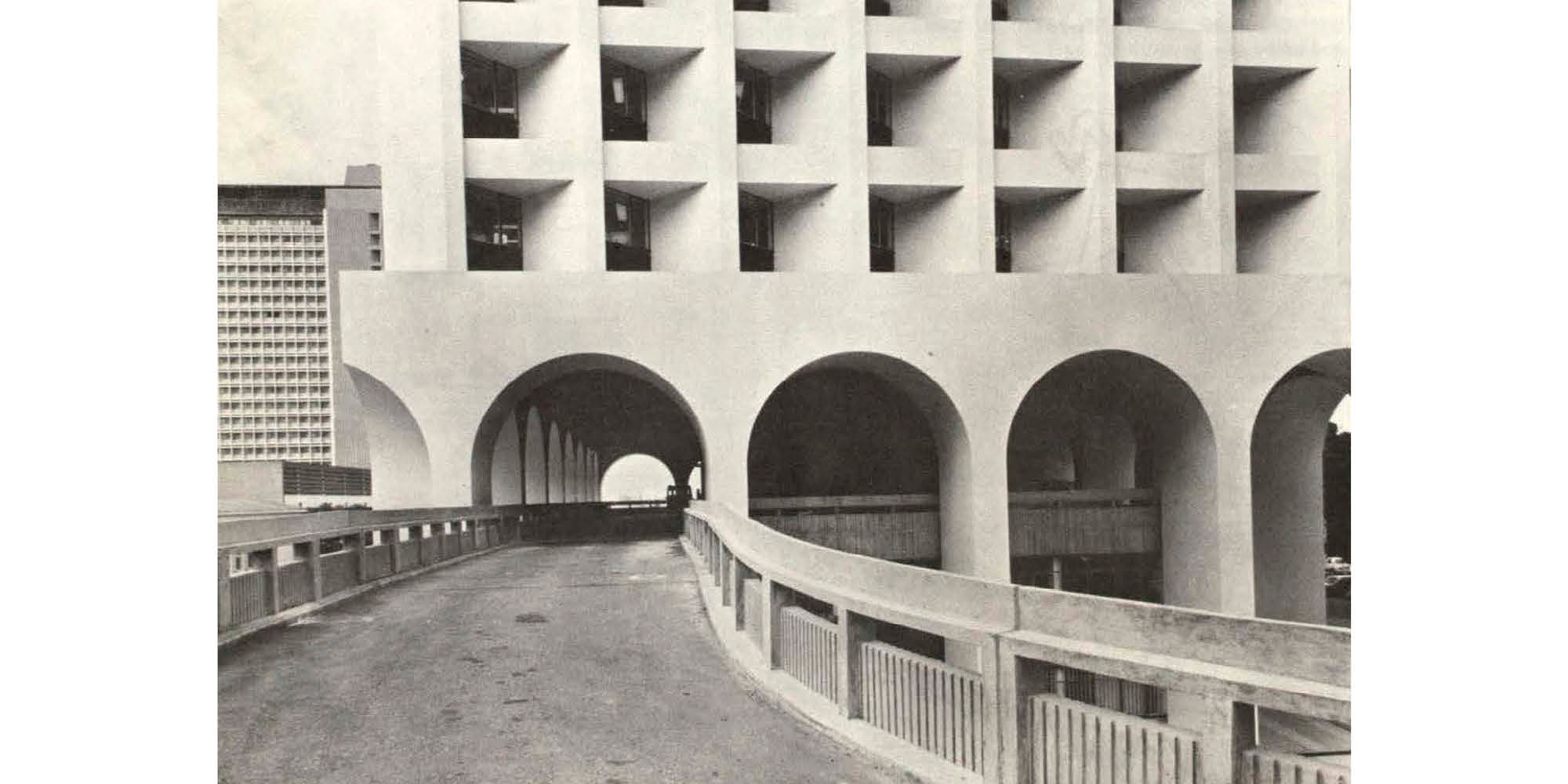

In the 1960s and 70s, car use had risen dramatically to become the leading mode of transportation in Hong Kong (the government had stopped issuing rickshaw licences in 1968). As an extension of this transportation trend, the Murray Building prioritised motor access with a car ramp. This ramp reflected a worldwide trend in bureaucratic architecture: the more senior an official, the closer their car was parked to their workstation and the shorter their walk.

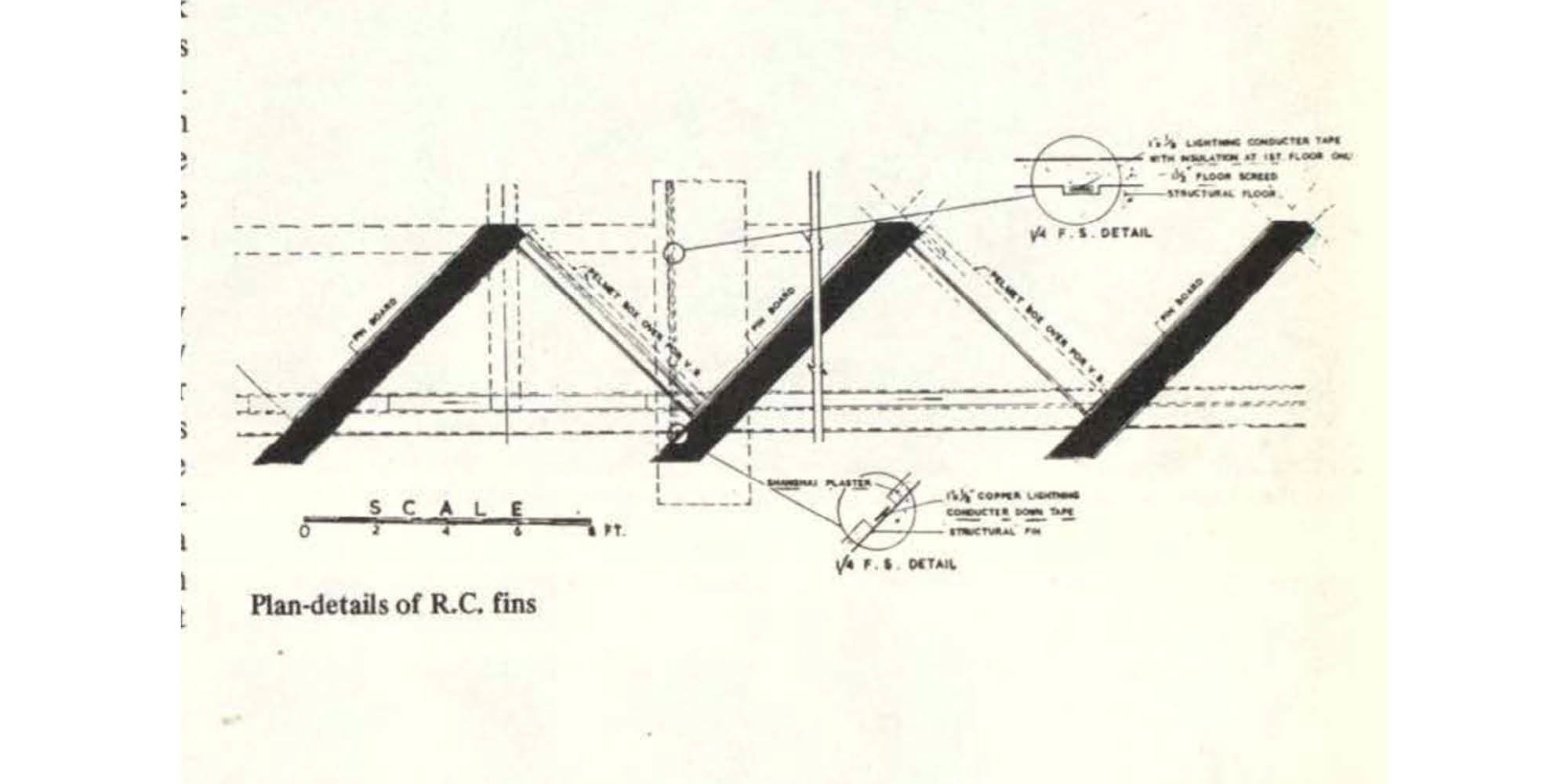

Alongside its urban situation, the Murray Building’s structure was formed in direct response to the climate of Hong Kong. Phillips designed fin walls that were placed at an angle of 45 degrees around the building, with windows recessed within the facade. Combining both structural and environmental engineering principles, Phillips’ design provided shading from the harsh tropical sunlight and, in turn, reduced the operational costs of cooling the building.

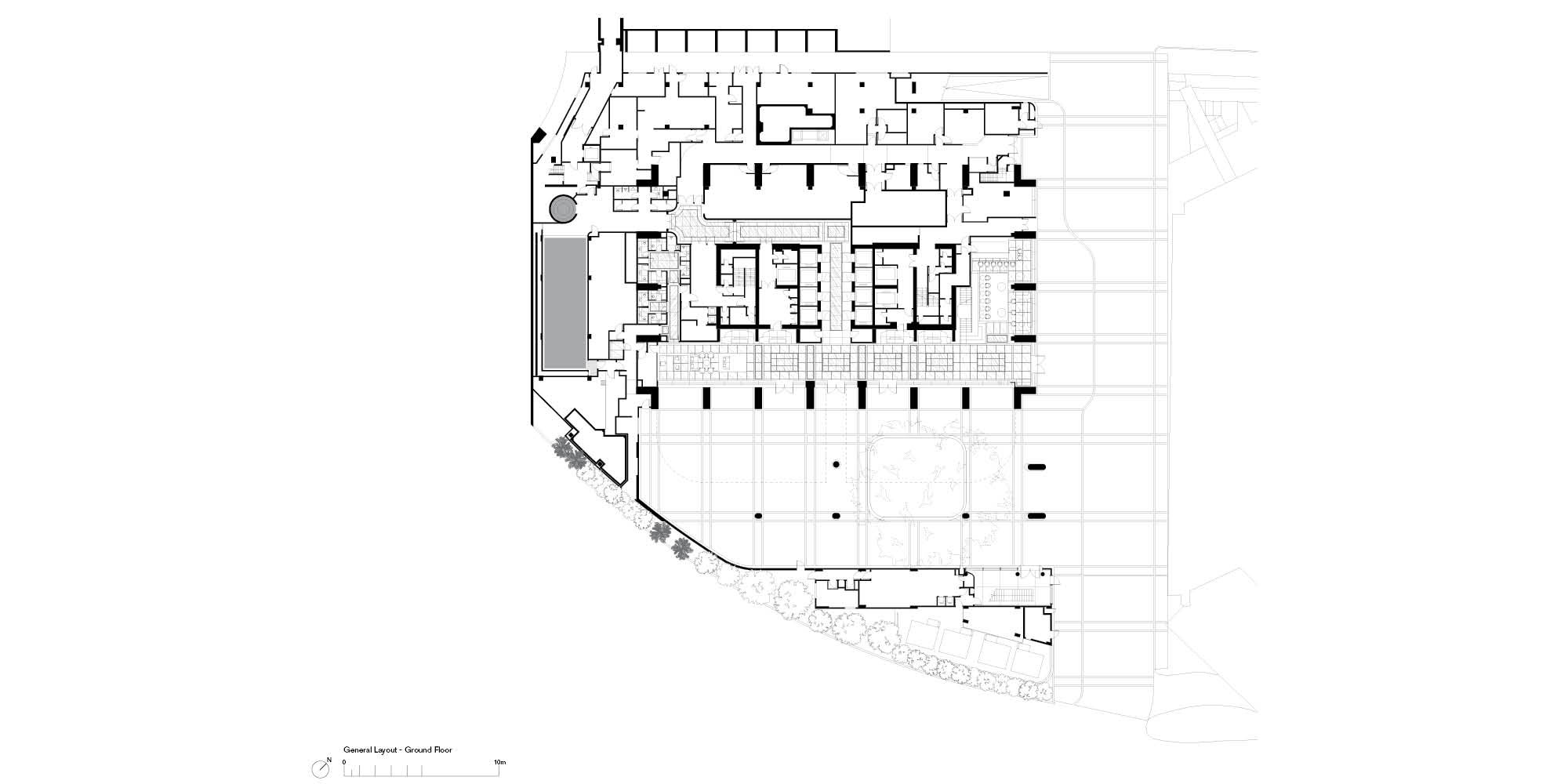

Adaptive re-use as reinterpretation of the plan

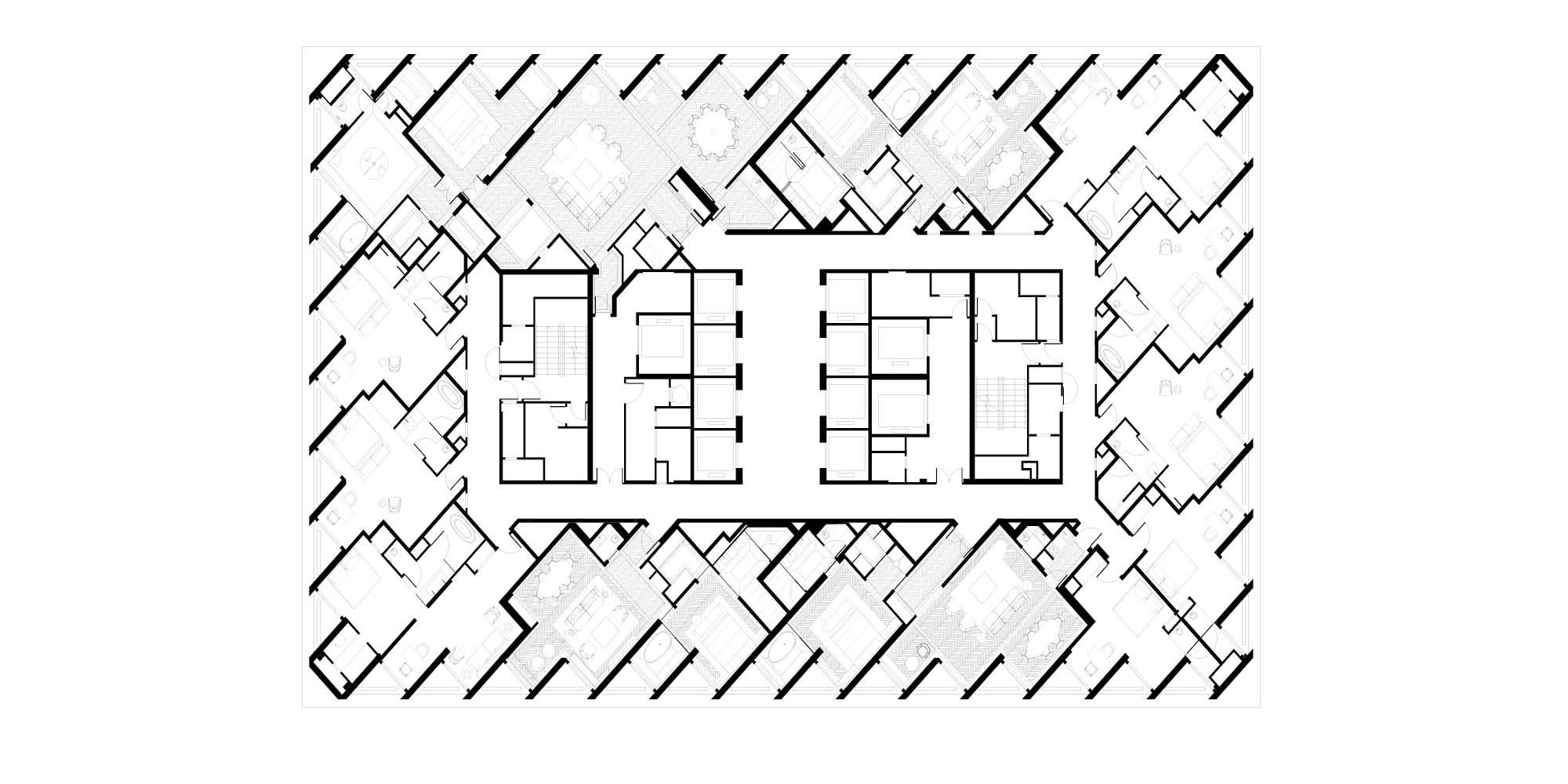

Any change in a building’s use requires a reconsideration of spatial layout – which must address changes in atmosphere and updates to environmental and technological services. To achieve an integrated outcome, all associated specialists must work closely throughout the design process. The layout of each hotel room in The Murray, for example, went through numerous iterations and tests. After several mock-ups and studies, the design team realised that a reorientation of the plan around the fins, and not the central core, was a way to unlock the Murray Building’s potential as a hotel.

Side-by-side comparisons are evidence of a much deeper process of understanding and working with the constraints and possibilities of a building.

By allowing the windows to lead the design, rather than inconvenience it, the hotel rooms celebrated the retained structure and were more generously spaced than a conventional room layout. The windows were also enlarged to enhance The Murray’s views of Hong Kong – a subtle shift in windowsill height transformed the overall experience of each hotel room. As Lawrence Wong, an architect in Foster + Partners’ Hong Kong studio, reflects: ‘This close engagement with the existing structure resulted in a unique spatial layout that could only have emerged from adaptive re-use.’

The Murray is situated opposite Foster + Partners’ Hongkong Shanghai Bank (1989), described by Deyan Sudjic as ‘the first true skyscraper outside of America’. It was also Foster Associates’ first commission outside of the United Kingdom. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Like Phillips’ finned façade, the Murray Building’s car ramp was also celebrated as an original feature. The ramp forms a tapered ceiling over the main entrance to the hotel and now acts as a walkway for visitors, transformed into a people- rather machine-focussed architectural device. As Ben Stevenson, Senior Interior Designer for the project, commented: ‘If we had a blank canvas, we may not have drawn a lobby with a tapered ceiling, nor, in all likelihood, would there be a ramp directly entering the building. That is the beauty and the magic of adaptive re-use: it constantly surprises you and pushes you to think flexibly and creatively.’

Re-use is not only a rewarding process for the architects, but the environment. The team calculated that reusing the 90-metre-high building saved 111,659 tonnes of embodied carbon – which is equivalent to planting 2.8 million seedlings and growing them for 10 years. Philips’ intelligent structure, furthermore, reduces solar gain by 70 percent when compared with a typical new building in Hong Kong; this, in turn, saves approximately 400 tonnes of carbon per year – amounting to 20,000 tonnes in the next fifty years.

Beyond the immediate built envelope of Phillips’ design, the adaptive re-use of this former office building also engaged with Hong Kong at an urban scale. Through The Murray’s arches, the formerly inaccessible basement and street levels were opened to pedestrians, and pathways were introduced to connect the site with the Botanic Gardens and tram station a few hundred metres away. The design team also protected the ‘Old and Valuable’ cherry tree at the front of the site to make it a centrepiece to the drop-off experience of the hotel. The tree was carefully released from its concrete confines – with the help of landscape architects – and continues to blossom each spring. As Stefano Cesario, Partner and Architect adds: ‘We love to get the best out of what is already there.’

The project’s transformation is expressed through ‘before and after’ photography. These are useful insofar as they demonstrate how a design has both sustained and changed – but such images alone can make adaptation seem deceptively straightforward. The practice of adaptive re-use happens between these moments; side-by-side comparisons are evidence of a much deeper process of understanding and working simultaneously with the constraints and possibilities of a building. And, as a project like The Murray demonstrates, a reconsideration of the building’s relationship with itself must also work alongside a reconsideration of the building’s relationship with its place. The motions between ‘before and after’, ‘old and new,’ ‘inside and outside’ are highly pressurised in adaptive re-use practice, and always implicit in a building, even as a project is completed.

Part 2: Disused Power Plant to Urban Rejuvenation Project

The initiative to adapt and reconnect existing buildings with their context was also Foster + Partners’ strategy in Ombú, a project for the Spanish infrastructure and energy company Acciona in Madrid (2020-2022). For this adaptive-re-use scheme, the existing building in question was originally constructed in 1905 by architect Luis de Landecho. It served as the gas plant for the Cerro de la Plata Sociedad Gasificadora Industrial and was part of a larger industrial complex near the Atocha station rail lines. Soon after the original use ceased, the general industrial area became neglected and undesirable, despite its prime location in Madrid and excellent access to public transportation.

By the time the site was purchased in 2017, Ombú was the last historic structure standing, narrowly saved from demolition. Its original use as a gas-fired powerplant was, understandably, no longer desirable, and the surrounding urban area had been relegated to often-vacant parking space. However, like The Murray, the main shell of the building – comprised of a load-bearing brick structure and a pitched steel truss roof – had remained in excellent condition since its construction 120 years before. Great care was taken to preserve and restore this structure – including over 10,000 tonnes of original brick – with environmental updates such as energy-efficient water, electrical, and fenestration systems integrated into the original envelope.

Emilio Ortiz Zaforas, a Partner and Architect based in Foster + Partners’ Madrid office, notes the clear benefits of investing in adaptive re-use: ‘By adapting buildings that would otherwise be demolished, we are not only preserving the architectural history of the city but celebrating and reimagining it in such a way that brings new visitors to the area.’ Pablo Urango Lillo, a Senior Partner and Architect, also in the Madrid office adds: ‘From the beginning, the client and the design team aligned on the common objective of sustainability.’

Initially envisioned as a single headquarters, the project had to pivot when the company’s workforce outgrew the space, leading to its development as an investment property. The lightweight structure inserted inside the space is made from sustainably sourced timber from local forests and allows for spatial flexibility, while also integrating lighting, ventilation and other services. The timber structure saves more than 1,600 tonnes of CO2, compared to a typical concrete one. It is also recyclable and demountable, meaning that it can adapt to further changes in use.

Landscaping at Ombú includes a new courtyard that, along with Madrid’s favourable climate, offers the option to comfortably work outdoors. The courtyard connects to a large 12,400 square-metre park with 350 trees featuring outdoor working spaces and areas for informal meetings sheltered by a green canopy of trees. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Adaptive re-use beyond the building

A perhaps less-heralded aspect of Foster + Partners’ work with existing buildings, where much of the focus is often directed to the restored or reimagined architecture, is the priority given to a revitalised – or in some cases entirely newly integrated – public realm. As Goldberger explains, these projects that engage with existing built spaces and urban fabric are frequently ‘designed to be experienced by more than their occupants and to connect to the city around them. Context is critical to this body of work, which is an acknowledgement in conceptual as well as practical terms that every building connects to things other than itself – to the larger world of people and public space as well as other buildings.’

As discussed, the practice believes that new additions should be demonstratively of their own time and, as such, articulate a clear philosophy about how contemporary mediations can be made within historical structures. When Foster + Partners have revitalised or reinvented public spaces as part of remodelled buildings, the interventions also create this spatial dialogue with history, as well as enhanced connections with civic life. As such, the interventions are vital contributors to a project’s expanded sustainability goals. Peter Buchanan explains further in his essays on Foster + Partners’ sustainable vision, the practice’s prioritisation of the public realm when working with existing buildings can ‘help us be better planetary citizens, and to live civic and cultural lives to the full while remaining grounded in local history and place. This is very much part of sustainability’s larger agenda.’

These ideas have been seen at The Murray, where a building once isolated on a traffic island has been rewoven into the city with new landscaping and pedestrian routes. At Ombú, while the building’s location and strong identity are undeniable assets, perhaps the greatest success of the project lies in the public ripple effect generated by the masterplan. As Taba Rasti, Senior Partner and Architect also based in Foster + Partners’ Madrid office, comments: ‘A key element of this is the public park, designed as a contribution to the city, it is just as significant as the structure itself.”

The park at Ombú has transformed the surrounding area, enhancing both its visual appeal and social impact. Spanning 12,400 square meters, the landscape was revitalised with the planting of 350 new trees and a wide variety of plant species. In just two years, the project has already shown remarkable results, with a noticeable increase in biodiversity – including the return of butterflies that hadn’t been seen in Madrid for 20 years.

Our buildings need not always be discarded, vacated, or demolished [...] they can have many lives if we allow them to.

‘Before’ and ‘after’ of Ombú. This view from the edge of the site powerfully illustrates the reclamation of once-neglected urban space in favour of enhanced civic life and ecological restoration. Local species have been carefully selected to reduce water consumption, which will come from local sources. © Rubén P. Bescós

‘Before’ and ‘after’ of Ombú. This view from the edge of the site powerfully illustrates the reclamation of once-neglected urban space in favour of enhanced civic life and ecological restoration. Local species have been carefully selected to reduce water consumption, which will come from local sources. © Rubén P. Bescós

One of the most sustainable projects by Foster + Partners, the scheme was presented at COP26 in Glasgow as a case study for the World Green Building Council. Its environmental impact is compatible with the original 2°C aim of the Paris Agreement and its carbon footprint has been carefully measured and controlled. The design reduces embodied carbon by 25 percent when compared to a new build over the whole life of the project while making allowances for future refurbishment. The operational energy is calculated to be 35 percent below normal expectations.

Adapting Ombú not only extended its lifespan and promoted sustainable design but reintroduced a stranded site and its history to a city that had previously neglected it. Adaptive re-use then, might also be considered a particular mode of attention – a way of tuning into what is already there, and asking how design might be corrected and connected where possible. It might be, to echo Buckminster Fuller’s famous edict, a way ‘to do more, with less’ – that is, to have a greater effect with fewer materials – but its effects resonate beyond just the material- or energy-related concerns of sustainability and the climate crisis. As Buchanan continues: ‘The primary drive of the sustainability agenda is to reconnect with everything, from nature and history, to other people and ourselves … Architecture becomes about reweaving as rich a web of relationships as possible: with us the users and passers-by, with nature and its phenomena (sun, wind, rain), and with history and culture, the city and its communities, and so on.’

Part 3: Abandoned Cinema to Retail Showstopper

As The Murray and Ombú infer, adaptive re-use is a way to invest in and celebrate the heritage of a site, while transforming its use to meet different, contemporary aims and reimagine its relationships with the city and its citizens. The third case study in this series is Apple Tower Theater, a project born from Foster + Partners’ collaborations with Apple, which showcases this practice at a granular, detail-oriented level.

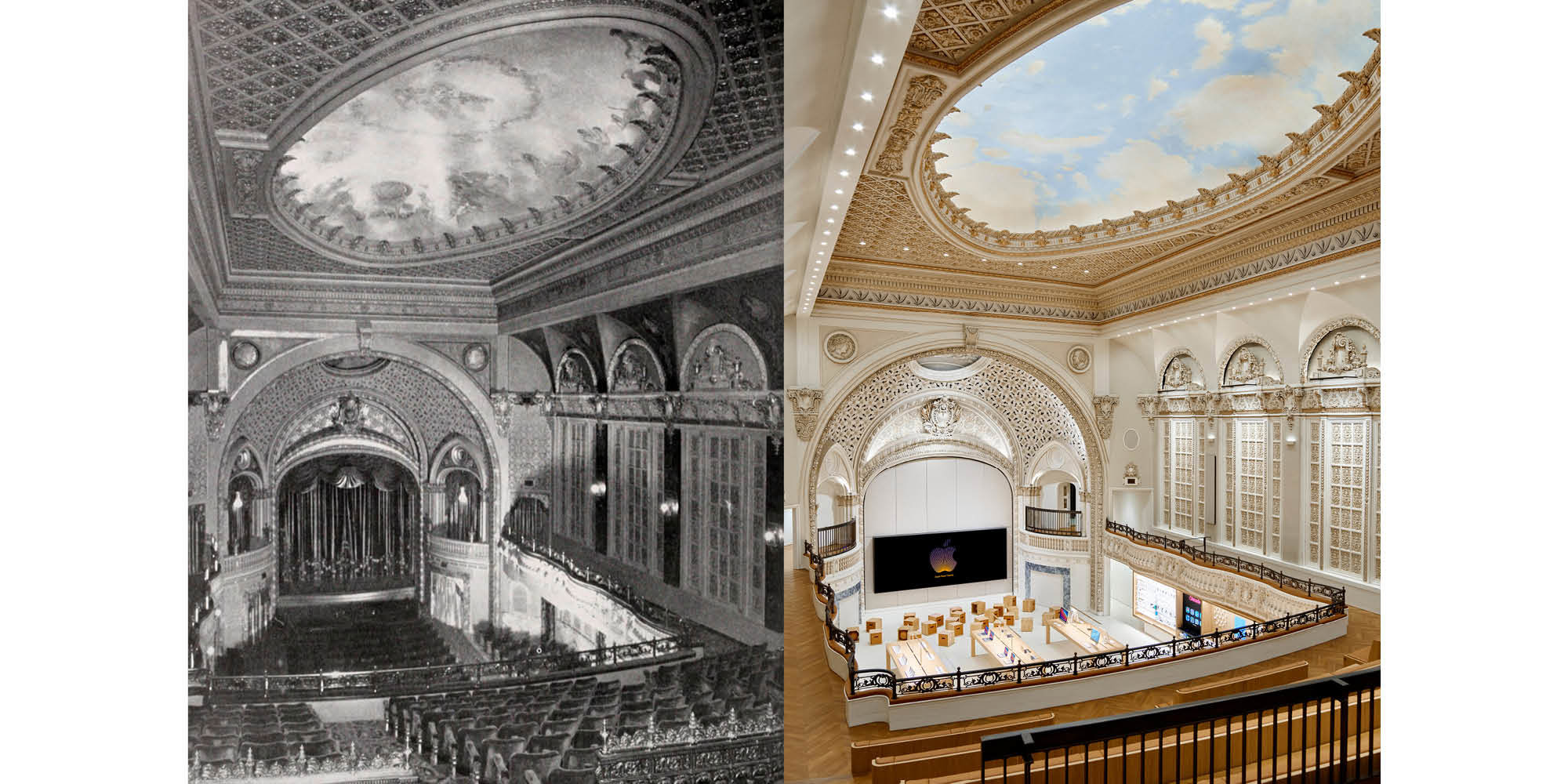

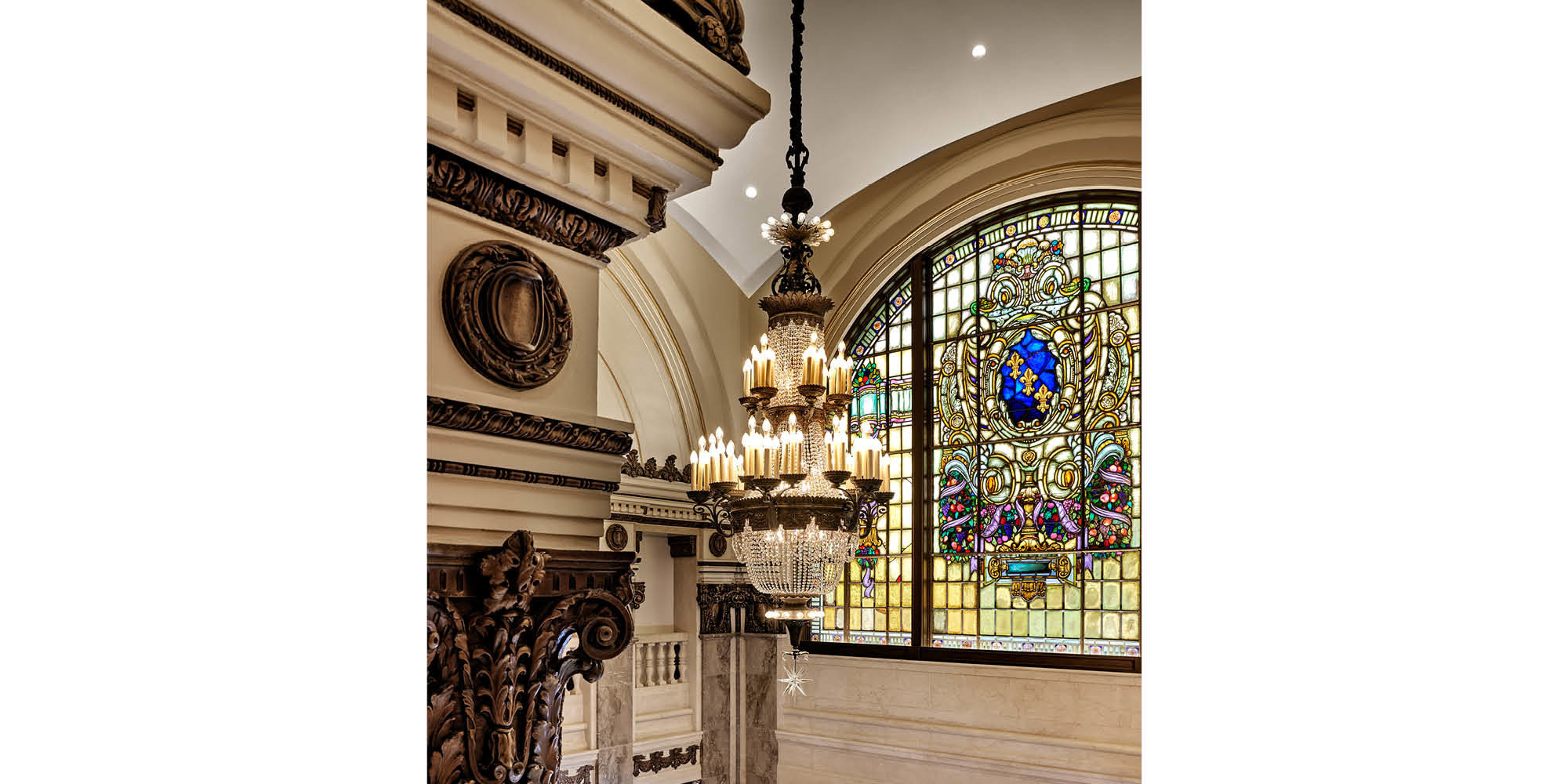

Originally home to the first theatre in Los Angeles wired for film with sound, the historic Tower Theater was designed in 1927 by renowned motion-picture theatre architect S. Charles Lee. Part of a wave of opulent movie theatres established in the area during the 1910s and 1920s, Tower Theater was nevertheless constrained by the square screen format common to the era and was underutilised for decades. After closing as a movie theatre in 1988, the space remained empty and unused. This project includes a great deal of restoration of the original building and asks how the past and the present might blend and find new resonances.

The building is designated as a Historic-Cultural Monument by the City of Los Angeles, meaning that the project’s preservation philosophy was guided by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation. Additionally, Foster + Partners organised a working group that met regularly with the Office of Historic Resources, the Los Angeles Conservancy and the Los Angeles Historic Theatre Foundation; this group discussed the theatre’s adaptation in not only its architectural sense but also as a community and cultural endeavour.

Interior and exterior views of the restored and reimagined Apple Tower Theatre in Los Angeles, California, USA. © Apple

Interior and exterior views of the restored and reimagined Apple Tower Theatre in Los Angeles, California, USA. © Apple

Interior and exterior views of the restored and reimagined Apple Tower Theatre in Los Angeles, California, USA. © Apple

The project included restoring the theatre’s corner clock tower and renovating the blade sign that projects from its side. Tower Theater’s terracotta facade was also cleaned and a canopy that extends over Broadway was rebuilt. Inside, a grand entry hall that was designed in the style of Charles Garnier’s Paris Opera House, complete with bronze handrails and marble columns, has been restored to its former splendour. An original stained-glass window with a pattern that includes coiled strips of film has also been painstakingly restored, along with a fresco of a blue and cloudy sky that arches over the double-height space. The team preserved as much historic fabric as feasible while allowing one form of spectacle and technological innovation to pave the way for another. Furthermore, the building’s existing condition, and changes made, were extensively documented and can be reversed.

The science and art of adaptive re-use

These case studies remind us that our buildings need not always be discarded, vacated, or demolished as we progress. Nor must they remain unaltered. Buildings can have many lives if we allow them to. Whether a reconfiguration of the floor plan (as in The Murray), a masterplan strategy extending beyond the built envelope (Ombú), or attention to the subtleties of heritage detail (Apple Tower Theater), or a combination of all three, adaptive re-use is a highly variable and complex practice which can be applied not only as a design strategy but part of the turn towards more sustainable ways of building.

As Christ Trott, Partner and Sustainability Engineer at Foster + Partners, reflects, each project should be approached with as much technical and analytical rigour as architectural and historical research:

It is vital to conduct a comprehensive whole-life-cycle analysis before making any claims about a building’s carbon expenditure. Like a doctor with a patient, [sustainability engineers] must test and diagnose the existing building before suggesting a way forward. This analysis allows us to make informed decisions – firstly, about whether adaptation is indeed the right course of action to take and, secondly, where further focus might be needed. The benefits of doing this in-house is that we can share this data with architects and closely monitor how these numbers change as a design does.

Whether analysing the carbon stored in the existing structure or released in manufacturing and transporting new materials for the building (such as concrete or steel), or calculating the costs of running the building, adaptive re-use presents a complex puzzle for sustainability engineers to solve. This is further complicated because energy supplies, building legislation, and environmental standards are frequently reassessed:

As national power grids move towards decarbonisation, the operational carbon cost of a building will decrease, meaning that a greater proportion of a building’s emissions will be attributed to its construction and adaptation (or demolition). Adaptation is one way to address this problem. However, on top of this, a building adapted today might not meet certain sustainability criteria in as soon as ten years’ time. So, at Foster + Partners, we have to design with all these moving targets in mind.

Adaptable thinking is required in adaptive re-use projects. It is the unique quality of adaptive re-use – both a highly responsive and highly recreative form of architectural and engineering practice – that makes it a science, and an art, of its own. It is a way of analysing, interpreting, and reimagining a building that is considered in its means, and no less ambitious in its ends.

Author

Stefano Cesario, Emilio Ortiz Zaforas, Taba Rasti, Ben Stevenson, Chris Trott, Pablo Urango Lillo, Lawrence Wong

Author Bio

Stefano Cesario is from Naples, Italy, and has lived in London since he came to study at The Bartlett School of Architecture, completing his architectural education with a First Class Degree and Diploma Commendations both in Design and Technical Studies. He is a RIBA qualified architect with an impressive experience within the practice spanning over a decade on a broad spectrum of projects ranging from urban masterplans, architecture, luxury interiors and bespoke details across the world. Stefano's experience is to lead both architecture and interior projects with an integrated approach that ties together all design disciplines, a holistic vision to creates innovative spaces for people to lead a better quality of life.

Emilio Ortiz Zaforas studied architecture at the Madrid School of Architecture, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, where he received the Academic Award for the highest marks. From 2005 to 2011 he worked in several practices in Spain, with involvement in international competitions and projects on site. Emilio joined Foster + Partners' London studio in 2011 and has worked on several projects around the world, including Comcast Technology Center in Philadelphia and the Stead Children's Hospital. In 2017 he moved to Foster + Partners' Madrid studio, where he has worked on projects including Ombú, Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts and the Hall of Realms for the Prado Museum.

Taba Rasti is a Senior Partner and co-directs Foster + Partners’ Madrid studio. She completed her studies at the Madrid School of Architecture (ETSAM) in 2003 and joined the practice in 2005. With over twenty years of experience, Taba has worked on a variety of projects at different scales and typologies, which range from cultural buildings to workplace and residential projects. Her speciality is the regeneration of historic buildings to give them a sustainable future. Taba is currently working on the restoration and extension of the Hall of Realms at the Prado Museum in Madrid, the restoration and extension of the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, residential projects in Portugal and cultural projects in the US, amongst others. Completed projects include a masterplan for the estate and restoration of the Chateau Margaux winery in Bordeaux and Ombú, a transformative office building built for the Spanish infrastructure and energy company ACCIONA, which was presented at COP26 in Glasgow as a case study for the World Green Building Council.

Chris Trott was born in Cardiff. Joining Foster + Partners allowed him to combine his qualifications in Civil Engineering and Environmental Services with his passion of bringing sustainability to design through highly integrated multidisciplinary collaboration. Chris is a yachtsman which allows him to combine his love of technology, and the natural environment with experiencing new local cultures. He is an active Christian and has a particular interest in how all faith communities can work together to benefit mankind and our natural environment.

Pablo Urango Lillo is co-director and partner in Madrid. He studied architecture at The Catholic University of America, Washington DC, graduating in 1999. And obtained a Master of Architectural Design at The Bartlett School of Architecture in 2000. He joined Foster + Partners in 2007, where he initially worked on the City of Justice in Madrid. Since, he has worked projects such as a Ski Resort in the pre-Pyrenees and Château Margaux in Bordeaux. He became a Partner in 2011 and is currently working on Ourense Train Station and Hall of Realms at Prado Museum.

Lawrence Wong grew up in Hong Kong and UK. He moved back to the Hong Kong studio in 2007 and has since worked on Kai Tak Cruise Terminal, Apple Store, The Murray in Hong Kong, CR University in Shenzhen, South Beach in Singapore, and currently seeing through construction for an office tower in Hong Kong.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George