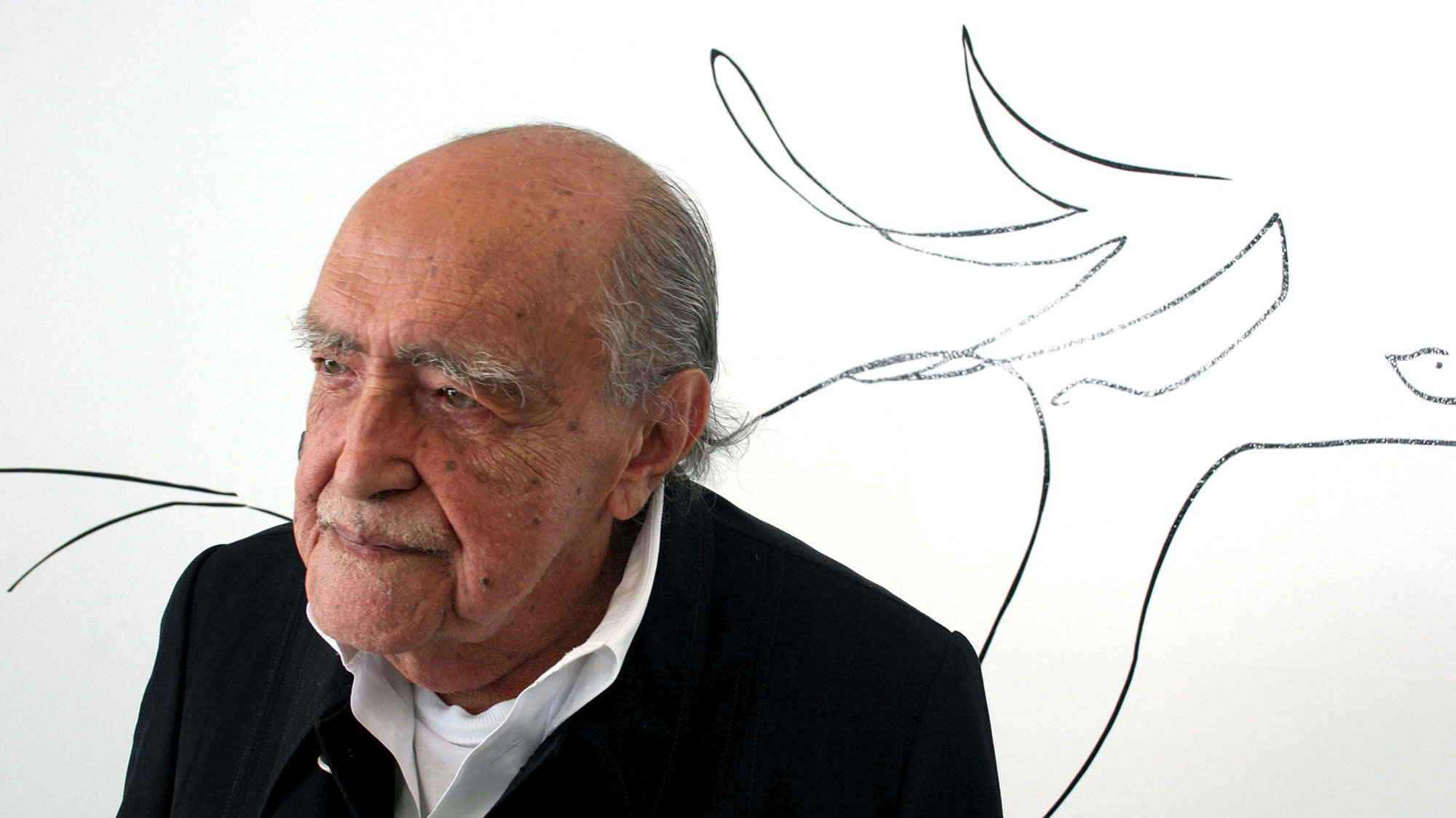

I was deeply saddened to learn of the death of Oscar Niemeyer. He was an inspiration to me – and to a generation of architects. Few people get to meet their heroes and I am grateful to have had the chance to spend time with him in Rio last year.

For architects schooled in the mainstream Modern Movement, he stood accepted wisdom on its head. Inverting the familiar dictum that ‘form follows function’, Niemeyer demonstrated instead that, ‘When a form creates beauty it becomes functional and therefore fundamental in architecture’.

It is said that when the pioneering Russian cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin visited Brasilia he likened the experience to landing on a different planet. Many people seeing Niemeyer’s city for the first time must have felt the same way. It was daring, sculptural, colourful and free − and like nothing else that had gone before. Few architects in recent history have been able to summon such a vibrant vocabulary and structure it into such a brilliantly communicative and seductive tectonic language.

One cannot contemplate Brasilia’s crown-like cathedral, for example, without being thrilled both by its formal dynamism and its structural economy, which combine to engender a sense almost of weightlessness from within, as the enclosure appears to dissolve entirely into glass. And what architect can resist trying to work out how the tapering, bone-like concrete columns of the Alvorada Palace are able to touch the ground so lightly. Brasilia is not simply designed, it is choreographed; each of its fluidly-composed pieces seems to stand, like a dancer, on its points frozen in a moment of absolute balance. But what I most enjoy in his work is that even the individual building is very much about the public promenade, the public dimension.

As a student in the early 1960s, I looked to Niemeyer’s work for stimulation; poring over the drawings of each new project. Fifty years later his work still has the power to startle us. His contemporary Art Museum at Niteroi is exemplary in this regard. Standing on its rocky promontory like some exotic plant form, it shatters convention by juxtaposing art with a panoramic view of Rio harbour. It is as if − in his mind − he had dashed the conventional gallery box on the rocks below, and challenged us to view art and nature as equals. I have walked the Museum’s ramps. They are almost like a dance in space, inviting you to see the building from many different viewpoints before you actually enter. I found it absolutely magic.

During our meeting last year, we spoke at length about his work – and he offered some valuable lessons for my own. It seems absurd to describe a 104 year old as youthful, but his energy and creativity were an inspiration. I was touched by his warmth and his great passion for life and for scientific discovery – he wanted to know about the cosmos and the world in which we live. In his words: "We are on board a fantastic ship!"

He told me that architecture is important, but that life is more important. And yet in the end his architecture is his ultimate legacy. Like the man himself, it is eternally youthful – he leaves us with a source of delight and inspiration for many generations to come.

Norman Foster

December 2012